- Home

- Charles King

The Black Sea

The Black Sea Read online

The Black Sea

ALSO BY CHARLES KING

The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture

Nations Abroad: Diaspora Politics and International Relations

in the Former Soviet Union (co-editor)

The Black Sea

A HISTORY

Charles King

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 0x2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Charles King 2004

First published 2004

First published in paperback 2005

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,

or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate

reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,

Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover

and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

Typeset by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India

Printed in Great Britain

on acid-free paper by

Ashford Colour Press Ltd., Gosport, Hampshire

ISBN 0-19-924161-9 978-0-19-924161-3

ISBN 0-19-928394-x (Pbk.) 9780-19-128394-1 (Pbk.)

1 3 5 7 9 1 0 8 6 4 2

For Lori

About the Author

Charles King is an Associate Professor in the School of Foreign Service and the Department of Government at Georgetown University, where he also holds the university’s Ion Raţiu Chair in Romanian Studies.

Contents

Acknowledgments

On Names

List of Plates

List of Maps

1. An Archaeology of Place

People and Water

Region, Frontier, Nation

Beginnings

Geography and Ecology

2. Pontus Euxinus, 700BC–AD500

The Edge of the World

“Frogs Around a Pond”

“A Community of Race”

How a Scythian Saved Civilization

The Voyage of Argo

"More Barbarous Than Ourselves"

Pontus and Rome

Dacia Traiana

The Expedition of Flavius Arrianus

The Prophet of Abonoteichus

3 Mare Maggiore, 500-1500

“The Scythian Nations are One”

Sea-Fire

Khazars, Rhos, Bulgars, and Turks

Business in Gazaria

Pax Mongolica

The Ship from Caffa

Empire of the Comneni

Turchia

An Ambassador from the East

4. Kara Deniz, 1500-1700

“The Source of All the Seas”

“To Constantinople—to be Sold!”

Domn, Khan, and Derebey

Sailors’ Graffiti

A Navy of Seagulls

5. Chernoe More, 1700-1860

Sea and Steppe

A Flotilla on Azov

Cleopatra Processes South

The Flight of the Kalmoucks

A Season in Kherson

Rear Admiral Dzhons

New Russia

Fever, Ague, and Lazaretto

A Consul in Trabzon

Crimea

6. Black Sea, 1860-1990

Empires, States, and Treaties

Steam, Wheat, Rail, and Oil

“An Ignoble Army of Scribbling Visitors”

Trouble on the Köstence Line

The Unpeopling

“The Division of the Waters”

Knowing the Sea

The Prometheans

Development and Decline

7. Facing the Water

Sources for Introductory Quotations

Bibliography and Further Reading

Index

Acknowledgments

The Armenian historian Agathangelos compared writing to a sea journey: Both writers and sailors willingly put themselves in peril and return home eager to tell stories about what they have encountered. I now understand what he meant.

More than once in this project, I stepped where I should not have gone. I loped into the gutted shell of a mosque in Nagorno-Karabakh, only later noticing the casing of a rocket-propelled grenade and wondering whether its unexploded colleagues might still be around. I jumped with equal abandon into the history of the Black Sea, knowing a lot about some of it, a little about more, and nothing about a great deal. The whole journey has been an instructive one, which is the point of writing anyway, and I am deeply grateful to all those who helped me along the way.

Dominic Byatt, my editor at Oxford University Press, got excited about the project when it was just an idea and, with Claire Croft, saw it through to the end. Susan Ferber in the New York office offered sage advice at a crucial point. Hakan and Ays, e Gül Altınay provided a wonderful retreat, the back room of their apartment on the Bosphorus, where I first thought about the book’s broad outlines.

Most of the text was researched and written beneath the statue of Herodotus in the Main Reading Room of the Library of Congress—there is no place like it—and I am very grateful to the library’s professional staff, including those in the Prints and Photographs Division, the Rare Book and Special Collections Reading Room, the Geography and Map Reading Room, the Africa and Middle East Reading Room, and the European Reading Room, in particular Grant Harris. The staff of the Hoover Institution archives, especially the director, Elena S. Danielson, were outstanding. Librarians and archivists at Georgetown University, the British Library, the Public Record Office (London), the Library of the Romanian Academy (Bucharest), the Central Historical Archive (Bucharest), and the Piłsudski Institute of America (New York) were generous with their time. Chris Robinson drew the maps.

I benefited from several seminars and conferences at which pieces of this book were presented, but I thank especially Nicholas Breyfogle, Abby Schrader, and Willard Sunderland, who allowed me to intrude on a conclave of Russian historians at Ohio State University in September 2001. The Fulbright fellowship program and Georgetown University made possible extended trips through the Balkans, Ukraine, Turkey, and the south Caucasus in 1998 and 2000. My travels before and since are also owed to the Raţiu Family Charitable Foundation, via its endowment to Georgetown. Tony Greenwood and Lawrence and Amy Tal provided agreeable lodging and conversation on my trips to and from the sea.

I have benefited greatly

from the knowledge of many professional colleagues and friends who indulged my naive questions or read parts of the manuscript, but none should be held responsible for my not heeding their advice. They include Alexandru Bologa, Anthony Bryer, Ian Colvin, Owen Doonan, Marc Morjé Howard, Christopher Joyner, Edward Keenan, Lori Khatchadourian, John McNeill, Willard Sunderland, and four anonymous reviewers for Oxford University Press. I am not a genuine expert in most of the specialist fields on which this book touches, so I am very grateful to those who are. Their painstaking work is recognized in the notes and bibliography.

A special word of gratitude goes to my frighteningly talented research assistants, Felicia Roşu and Adam Tolnay. May they finish their doctorates and find the jobs they deserve. Another Georgetown graduate student, Mirjana Morosini-Dominick, helped with an important translation.

On Names

Around the Black Sea, spelling bees can be political events, so a word on my use of language is in order.

The chapter titles in this book are some of the many names by which the sea has been known. The earliest ancient Greek name, Pontos Axeinos (the dark or somber sea), may have been adopted from an older Iranian term. It may also have reflected sailors’ apprehension about sailing its stormy waters, as well as the simple fact that the water itself, because of the sea’s great depth, appears darker than in the shallower Mediterranean. How that name was transformed into the Pontus Euxinus (the welcoming sea) of later Greek and Latin writers is uncertain. Perhaps the irony was intentional; perhaps it was just wishful thinking.

The most common name in Byzantine sources was simply Pontos (the sea), a usage that made its way also into Arabic texts as bahr Buntus, which amounts to the intriguingly redundant Sea Sea. But many other names were in use in the Middle Ages, especially in Arabic and Ottoman writings, and were often associated with particularly prominent cities, whence Sea of Trabzon and Sea of Constantinople. The designation Great Sea also appears in the Middle Ages in various forms, including the Italian Mare Maius and Mare Maggiore. Still other names were derived from whichever group happened to be dominant around the coasts at any particular time—or whichever group an author wanted his reader to think was dominant. Hence, labels such as the Scythian Sea, the Sarmatian Sea, the Sea of the Khazars, of the Rhos, of the Bulgars, of the Georgians, and others. In Arabic sources, the Mediterranean was, by contrast, the Sea of the Romans (that is, of the Byzantines).

Compared to all these, Black Sea is rather young, at least as a widely accepted name. It appears in early Ottoman sources in various forms, and was perhaps in colloquial usage from very early in Ottoman history. Its first appearance in a west European language comes at the end of the fourteenth century, but it did not receive broad currency until three centuries later. Before then, European labels were mainly adaptations of those of the classical age, such as Pontus and Euxine in English, terms that still have poetic connotations which the pedestrian Black Sea lacks. “Like to the Pontic sea, whose icy current and compulsive course ne’er feels retiring ebb …,” says Shakespeare’s enraged Othello, “even so my bloody thoughts, with violent pace, shall ne’er look back….”

But why “black?” No one knows for sure, but there are at least three major speculations. One is that it was simply a throwback to the earliest Iranian/Greek designation, which had been preserved among the inhabitants of the Black Sea littoral long after writers in mainland Greece and Rome had come to use the more inviting Euxinus. That older name could have been carried to the west during the Turkic migrations into Anatolia, eventually becoming the Ottoman Kara Deniz, (the black or dark sea). A second view is that kara, which also has the connotation “great” or “terrible,” was taken into Ottoman usage from the common Great Sea label used by medieval European, especially Italian, sailors and mapmakers. A third explanation is related to the color-coded geography of Eurasian steppe peoples. In this schema, which has its roots in China, the points of the compass are associated with particular colors: black for north, white for west, red for south, sometimes blue for east. Although how this system works obviously depends on one’s vantage point, the Ottoman designation of the sea to their north as “black” may be rooted in this Eurasian tradition, either as an echo of the Ottomans’ own distant past as Eurasian nomads or a convention that later Ottoman geographers adopted from the Mongols. In Ottoman and also in modern Turkish, the Mediterranean is, by contrast, known as the White Sea (Ak Deniz).

As Russians and west Europeans became more familiar with the sea in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they probably translated into their own languages the term that the region’s major power was using at the time. That borrowing was probably replicated in other languages of the region, which were undergoing the process of modernization and standardization at roughly the same time. The result of this convoluted history is that today the sea’s many names are really, in translation, the same: Karadeniz in Turkish, Maure Thalassa in modern Greek, Cherno More in Bulgarian, Marea Neagra in Romanian, Chorne More in Ukrainian, Chernoe More in Russian, shavi zghva in Georgian—all of which mean literally “black sea.”

For place names, I generally use the form appropriate to a particular historical period. Hence, Trapezus in antiquity becomes Trebizond in the Middle Ages and Trabzon today. Where there is more than one name in use in any period, I use the one that is more widely known; Greek names, for example, usually appear in their Latinized forms. I use Constantinople before 1453 and Istanbul after, even though the older name was common in various forms even during the Ottoman period. Older English spellings—such as “Sebastopol” or “Batoum”—have been replaced by their modern forms, except in direct quotations; the same goes for names of cultural groups (“Tartars,” for example). By Greeks I usually mean people who probably spoke a variety of the Greek language, even if they had little conception of themselves as Greek in a modern national sense. I am careful to use Ottoman to mean associated with the Ottoman empire; it is not the same thing as Turk which, until the twentieth century, is problematic as a designation for people whom we would now call Turkish-speakers. I have retained the unfashionable word Turkoman (rather than Turkmen) to refer to Turkic nomads and their rulers in Anatolian history, in order to distinguish them from the people and culture of the modern country of Turkmenistan in central Asia.

Languages that use alphabets other than the Latin one are transliterated using a simplified version of the Library of Congress systems; no final soft-sign in most Russian words, for example. I have retained diacritical marks for languages that use them in the Latin script. Approximate pronunciations of the more troublesome letters are as follows:

â, î “i” in cousin Romanian

a “a” in about Romanian

i “i” in cousin Turkish

ö “oeu” in French oeuvre Turkish

ü “u” in French tu Turkish

c “ch” in church before e

or i; otherwise “k” in

kit Romanian

c “j” in jam Turkishs

ç “ch” in church Turkish

ch “k” in kit before e or i Romanian

g “j” in jam before e or i;

otherwise “g” in goat Romanian

ğ silent, but lengthens

preceding vowel Turkish

gh “g” in goat before e or i Romanian

ş “sh” in ship Romanian and Turkish

ţ “ts” in cats Romanian

Unless otherwise noted, ancient sources in the footnotes refer to the translations in the Loeb Classical Library series published by Harvard University Press. References to ancient and Byzantine-era texts usually indicate sections rather than pages.

List of Plates

(between pages 138 and 139)

1 AND 2 Travelers to and from the Black Sea World. Anacharsis image: Prof. Dr. Lutz Geldsetzer from his private book collection: www.phil-fak.uni-duesseldorf.de/philo/geldsetzer/index.html. Statue of Ovid: picture courtesy of Charles King.

3 The Dacian King D

ecebal Commits Suicide. Courtesy of Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Rome.

4 Byzantine Sailors Employing “Sea-Fire” Against an Enemy Ship. Courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid.

5 The Striking Soumela Monastery, Inland From the Port City of

Trabzon. ©David Samuel Robbins/CORBIS.

6 A Circassian Woman in Traditional Costume. Courtesy of Syndics of Cambridge University Library from Edmund Spencer, Turkey, Russia, the Black Sea and Circassia (1855), XIX.40.23.

7 Transport by Land and Sea. Courtesy of the British Library, Guillaume le Vasseur Beauplan, Description of Ukraine (1732), 566kb.

8 The Bust of John Paul Jones by Houdon. Courtesy of John Paul Jones Birthplace Museum Trust.

9 Buchholtz, Allegory of the Victory of the Russian Fleet. Courtesy of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

10 Rough Travelling: A “Nocturnal Battle with Wolves” in Moldova, from a Travelogue by Edmund Spencer, 1854. Courtesy of Syndics of Cambridge University Library from Edmund Spencer, Turkey, Russia, the Black Sea and Circassia (1855), XIX.40.23.

11 Cossack Bay at Balaklava during the Crimean War. Courtesy of Roger Frenton Crimean War Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

12 Divers with Apparatus and Support Team at the Ottoman Imperial Naval Arsenal, circa 1890, from the Photo Albums of Sultan Abdulhamit II. Courtesy of Abdul Hamid Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

13 A Hand-Dug Oil Pit in Romania, 1923. Courtesy of Carpenter Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

14 A Ship Filled with Refugees and White Army Soldiers Fleeing Sevastopol during the Russian Civil War, 1919. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

15 Fortunes of War: Refugee children from the Russian empire. Courtesy of American Relief Administration, European Operations Records, Hoover Institution Archives.

List of Maps

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier

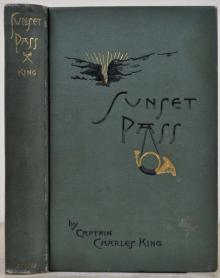

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land

Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days

From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days Annie o' the Banks o' Dee

Annie o' the Banks o' Dee The Black Sea

The Black Sea Under Fire

Under Fire Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier

Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War

Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68.

Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68. Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains A War-Time Wooing: A Story

A War-Time Wooing: A Story The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair

The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair Kitty's Conquest

Kitty's Conquest A Trooper Galahad

A Trooper Galahad Waring's Peril

Waring's Peril Marion's Faith.

Marion's Faith. Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila

Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul