- Home

- Charles King

Kitty's Conquest

Kitty's Conquest Read online

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Mary Meehan and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Thisfile was produced from images generously made availableby The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

KITTY'S CONQUEST.

BY CHARLES KING, U.S.A.,

AUTHOR OF "THE COLONEL'S DAUGHTER."

PHILADELPHIA: J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY. 1890.

Copyright. 1884, by J. B. LIPPINCOTT & CO.

PREFACE.

The incidents of this little story occurred some twelve years ago, andit was then that the story was mainly written.

If it meet with half the kindness bestowed upon his later work it willmore than fulfil the hopes of

THE AUTHOR.

February, 1884.

KITTY'S CONQUEST.

CHAPTER I.

It was just after Christmas, and discontentedly enough I had left mycosy surroundings in New Orleans, to take a business-trip through thecounties on the border-line between Tennessee and northern Mississippiand Alabama. One sunny afternoon I found myself on the "freight andpassenger" of what was termed "The Great Southern Mail Route." We hadbeen trundling slowly, sleepily along ever since the conductor's "allaboard!" after dinner; had met the Mobile Express at Corinth when theshadows were already lengthening upon the ruddy, barren-lookinglandscape, and now, with Iuka just before us, and the warning whistle ofthe engine shrieking in our ears with a discordant pertinacity attainedonly on our Southern railroads, I took a last glance at the sun justdisappearing behind the distant forest in our wake, drew the lastbreath of life, from my cigar, and then, taking advantage of the halt atthe station, strolled back from the dinginess of the smoking-car to morecomfortable quarters in the rear.

There were only three passenger-cars on the train, and, judging from thescarcity of occupants, one would have been enough. Elbowing my waythrough the gaping, lazy swarms of unsavory black humanity on theplatform, and the equally repulsive-looking knots of "poor white trash,"the invariable features of every country stopping-place south of Masonand Dixon, I reached the last car, and entering, chose one of a dozenempty seats, and took a listless look at my fellow-passengers,--six inall,--and of them, two only worth a second glance.

One, a young, perhaps very young, lady, so girlish, _petite_, and prettyshe looked even after the long day's ride in a sooty car. Her seat wassome little distance from the one into which I had dropped, but that wasbecause the other party to be depicted was installed within two of her,and, with that indefinable sense of repulsion which induces alltravellers, strangers to one another, to get as far apart as possible onentering a car, I had put four seats 'twixt him and me,--and afterwardswished I hadn't.

It _was_ rude to turn and stare at a young girl,--travelling alone, too,as she appeared to be. I did it involuntarily the first time, and foundmyself repeating the performance again and again, simply because Icouldn't help it,--she looked prettier and prettier every time.

A fair, oval, tiny face; a somewhat supercilious nose, andnot-the-least-so mouth; a mouth, on the contrary, that even though itspretty lips were closed, gave one the intangible yet positive assuranceof white and regular teeth; eyes whose color I could not see becausetheir drooping lids were fringed with heavy curving lashes, but whichsubsequently turned out to be a soft, dark gray; and hair!--hair thatmade one instinctively gasp with admiration, and exclaim (mentally), "Ifit's _only_ real!"--hair that rose in heavy golden masses above andaround the diminutive ears, almost hiding them from view, and fell inbraids (not braids either, because it _wasn't_ braided) and rolls--onlythat sounds breakfasty--and masses again,--it must do for both,--heavygolden masses and rolls and waves and straggling offshoots anddisorderly delightfulness all down the little lady's neck, and, landingin a lump on the back of the seat, seemed to come surging up to the topagain, ready for another tumble.

It looked as though it hadn't been "fixed" since the day before, and yetas though it would be a shame to touch it; and was surmounted, "satupon," one might say, by the jauntiest of little travelling hats of somedark material (don't expect a bachelor, and an elderly one at that, tobe explicit on such a point), this in turn being topped by the pertestlittle mite of a feather sticking bolt upright from a labyrinth ofbeads, bows, and buckles at the side.

More of this divinity was not to be viewed from my post of observation,as all below the fragile white throat with its dainty collar and thehandsome fur "boa," thrown loosely back on account of the warmth of thecar, was undergoing complete occultation by the seats in front; yetenough was visible to impress one with a longing to become acquaintedwith the diminutive entirety, and to convey an idea of cultivation andrefinement somewhat unexpected on that particular train, and in thatutterly unlovely section of the country.

Naturally I wondered who she was; where she was going; how it happenedthat she, so young, so innocent, so be-petted and be-spoilt inappearance, should be journeying alone through the thinly settledcounties of upper Mississippi. Had she been a "through" passenger, shewould have taken the express, not this grimy, stop-at-every-shanty,slow-going old train on which we were creeping eastward.

In fact, the more I peeped, the more I marvelled; and I found myselfalmost unconsciously inaugurating a detective movement with a view toascertaining her identity.

All this time mademoiselle was apparently serenely unconscious of myscrutiny and deeply absorbed in some object--a book, probably--in herlap. A stylish Russia-leather satchel was hanging among the hooks aboveher head,--evidently her property,--and those probably, too, were herinitials in monogram, stamped in gilt upon the flap, too far off for myfading eyes to distinguish, yet tantalizingly near.

Now I'm a lawyer, and as such claim an indisputable right to exercisethe otherwise feminine prerogative of yielding to curiosity. It's ourbusiness to be curious; not with the sordid views and mercenary intentsof Templeton Jitt; but rather as Dickens's "Bar" was curious,--affably,apologetically, professionally curious. In fact, as "Bar" himself said,"we lawyers _are_ curious," and take the same lively interest in theaffairs of our fellow-men (and women) as maiden aunts are popularlybelieved to exercise in the case of a pretty niece with a dozen beaux,or a mother-in-law in the daily occupations of the happy husband of hereldest daughter. Why need I apologize further? I left my seat;zig-zagged down the aisle; took a drink of water which I didn't want,and, returning, the long look at the monogram which I _did_.

There they were, two gracefully intertwining letters; a "C" and a "K."Now was it C. K. or K. C.? If C. K., what did it stand for?

I thought of all manner of names as I regained my seat; some pretty,some tragic, some commonplace, none satisfactory. Then I concluded tobegin over; put the cart before the horse, and try K. C.

Now, it's ridiculous enough to confess to it, but Ku-Klux was the firstthing I thought of; K. C. didn't stand for it at all, but Ku-Klux_would_ force itself upon my imagination. Well, everything _was_ Ku-Kluxjust then. Congress was full of them; so was the South;--Ku-Klux hadbrought me up there; in fact I had spent most of the afternoon inplanning an elaborate line of defence for a poor devil whom I knew to beinnocent, however blood-guilty might have been his associates. Ku-Kluxhad brought that lounging young cavalryman (the other victim reservedfor description), who--confound him--had been the cause of my taking ametaphorical back seat and an actual front one on entering the car; butKu-Klux couldn't have brought _her_ there; and after all, what businesshad I bothering my tired brains over this young beauty? I was nothing toher, why should she be such a torment to me?

In twenty minutes we would be due at Sandbrook, and there I was to leavethe train and jog across the country to the plantation of Judge Summers,an old friend of my father's and of mine, wh

o had written me to visithim on my trip, that we might consult together over some intricatecases that of late had been occupying his attention in that vicinity. Infact, I was too elderly to devote so much thought and speculation to adamsel still in her teens, so I resolutely turned eyes and tried to turnthoughts to something else.

The lamps were being lighted, and the glare from the one overhead fellfull upon my other victim, the cavalryman. I knew him to be such fromthe crossed sabres in gold upon his jaunty forage cap, and the heavyarmy cloak which was muffled cavalier-like over his shoulders,displaying to vivid advantage its gorgeous lining of canary color, yetcompletely concealing any interior garments his knightship might bepleased to wear.

Something in my contemplation of this young warrior amused me to thatextent that I wondered he had escaped more than a casual glance before.Lolling back in his seat, with a huge pair of top boots spread out uponthe cushion in front, he had the air, as the French say, of thoroughself-appreciation and superiority; he was gazing dreamily up at the lampoverhead and whistling softly to himself, with what struck me forciblyas an affectation of utter nonchalance; what struck me still moreforcibly was that he did not once look at the young beauty so closebehind him; on the contrary, there was an evident attempt on his partto appear sublimely indifferent to her presence.

Now that's very unusual in a young man under the circumstances, isn'tit? I had an idea that these Charles O'Malleys were heart-smashers; butthis conduct hardly tallied with any of my preconceived notions on thesubject of heart-smashing, and greatly did I marvel and conjecture as tothe cause of this extraordinary divergence from the manners and customsof young men,--soldiers in particular, when, of a sudden, Mars arose,threw off his outer vestment, emerged as it were from a golden glory ofyellow shelter-tent; discovered a form tall, slender, graceful, anderect, the whole clad in a natty shell-jacket and riding-breeches;stalked up to the stove in the front of the car; produced, filled, andlighted a smoke-begrimed little meerschaum; opened the door with a snap;let himself out with a bang; and disappeared into outer darkness.

Looking quickly around, I saw that the fair face of C. K. or K. C. wasuplifted; furthermore, that there was an evident upward tendency on thepart of the aforementioned supercilious nose, entirely out of proportionwith the harmonious and combined movement of the other features;furthermore, that the general effect was that of maidenly displeasure;and, lastly, that the evident object of such divine wrath was, beyondall peradventure, the vanished knight of the sabre.

"Now, my lad," thought I, "what have you done to put your foot in it?"

Just then the door reopened, and in came, not Mars, but the conductor;and that functionary, proceeding direct to where she sat, thus addressedthe pretty object of my late cogitations (I didn't listen, but I heard):

"It'll be all right, miss. I telegraphed the judge from Iuka, and reckonhe'll be over with the carriage to meet you; but if he nor none of thefolks ain't there, I'll see that you're looked after all right. Old JakeBiggs'll be there, most like, and then you're sure of getting over tothe judge's to-night anyhow."

Here I pricked up my ears. Beauty smilingly expressed her gratitude,and, in smiling, corroborated my theory about the teeth to the mostsatisfactory extent.

"The colonel," continued the conductor, who would evidently have beenglad of any excuse to talk with her for hours, "the colonel, him and Mr.Peyton, went over to Holly Springs three days ago; but the smash-up onthe Mississippi Central must have been the cause of their not getting tothe junction in time to meet you. That's why I brought you along on thistrain; 'twasn't no use to wait for them there."

"Halloo!" thought I at this juncture, "here's my chance; he means JudgeSummers by 'the judge's,' and 'the colonel' is Harrod Summers, ofcourse, and Ned Peyton, that young reprobate who has been playing fastand loose among the marshals and sheriffs, is the Mr. Peyton he speaksof; and this must be some friend or relative of Miss Pauline's going tovisit her. The gentlemen have been sent to meet her, and have beendelayed by that accident. I'm in luck;" so up I jumped, elbowed theobliging conductor to one side; raised my hat, and introducedmyself,--"Mr. Brandon, of New Orleans, an old friend of Judge Summers,on my way to visit him; delighted to be of any service; pray accept myescort," etc., etc.--all somewhat incoherent, but apparentlysatisfactory. Mademoiselle graciously acknowledged my offer; smilinglyaccepted my services; gave me a seat by her side; and we were soonbusied in a pleasant chat about "Pauline," her cousin, and "Harrod," herother cousin and great admiration. Soon I learned that it was K. C.,that K. C. was Kitty Carrington; that Kitty Carrington was JudgeSummers's niece, and that Judge Summers's niece was going to visit JudgeSummers's niece's uncle; that they had all spent the months of Septemberand October together in the north when she first returned from abroad;that she had been visiting "Aunt Mary" in Louisville ever since, andthat "Aunt Mary" had been with her abroad for ever so long, and was justas good and sweet as she could be. In fact, I was fast learning all mycharming little companion's family history, and beginning to feeltolerably well acquainted with and immensely proud of her, when the dooropened with a snap, closed with a bang, and, issuing from outerdarkness, re-entered Mars.

Now, when Mars re-entered, he did so pretty much as I have seen hisbrother button-wearers march into their company quarters on inspectionmorning, with an air of determined ferocity and unsparing criticism; butwhen Mars caught sight of me, snugly ensconced beside the only belle onthe train, the air suddenly gave place to an expression of astonishment.He dropped a gauntlet; picked it up; turned red; and then, with suddenresumption of lordly indifference, plumped himself down into his seat inas successful an attempt at expressing "Who cares?" without saying it,as I ever beheld.

Chancing to look at Miss Kitty, I immediately discovered that a littlecloud had settled upon her fair brow, and detected the nose on anotherrise, so said I,--

"What's the matter? Our martial friend seems to have fallen under theban of your displeasure," and then was compelled to smile at thevindictiveness of the reply:

"_He!_ he has indeed! Why, he had the impertinence to speak to me beforeyou came in; asked me if I was not the Miss Carrington expected atJudge Summers's; actually offered to escort me there, as the colonel hadfailed to meet me!"

"Indeed! Then I suppose I, too, am horribly at fault," said I, laughing,"for I've done pretty much the same thing?"

"Nonsense!" said Miss Kit. "Can't you understand? He's a Yankee,--aYankee officer! You don't suppose I'd allow myself, a Southern girlwhose home was burnt by Yankees and whose only brother fought allthrough the war against them,--you don't suppose I'd allow myself toaccept any civility from a Yankee, do you?" and the bright eyes shot avengeful glance at the dawdling form in front, and a terrific poutstraightway settled upon her lips.

Amused, yet unwilling to offend, I merely smiled and said that it hadnot occurred to me; but immediately asked her how long before myentrance this had happened.

"Oh, about half an hour; he never made more than one attempt."

"What answer did you give him?"

"Answer!--why! I couldn't say much of anything, you know, but merelytold him I wouldn't trouble him, and said it in such a way that he knewwell enough what was meant. He took the hint quickly enough, and turnedred as fire, and said very solemnly, 'I ask your pardon,' put on his capand marched back to his seat." Here came a pretty little imitation ofMars raising his chin and squaring his shoulders as he walked off.

I smiled again, and then began to think it all over. Mars was a totalstranger to me. I had never seen him before in my life, and, so long aswe remained on an equal footing as strangers to the fair K. C., I hadbeen disposed to indulge in a little of the usual jealousy of "militaryinterference," and, from my exalted stand-point as a man of the worldand at least ten years his senior in age, to look upon him as a boy withno other attractions than his buttons and a good figure; but Beauty'sanswer set me to thinking. I was a Yankee, too, only she didn't know it;if she had, perhaps Mars would have stood the better chance

of the two.I, too, had borne arms against the Sunny South (as a valiant militia-manwhen the first call came in '61), and had only escaped wearing theuniform she detested from the fact that our regimental rig was gray, andmy talents had never conspired to raise me above the rank oflance-corporal. I, too, had participated in the desecration of the"sacred soil" (digging in the hot sun at the first earthworks we threwup across the Long Bridge); in fact, if she only knew it, there wasprobably more reason, more real cause, for resentment against me, thanagainst the handsome, huffy stripling two seats in front.

He was a "Yank," of course; but judging from the smooth, ruddy cheek,and the downiest of downy moustaches fringing his upper lip, had butjust cut loose from the apron-strings of his maternal West Point. Why!he must have been at school when we of the old Seventh tramped downBroadway that April afternoon to the music of "Sky-rockets," halfdrowned in stentorian cheers. In fact, I began, in the few seconds ittook me to consider this, to look upon Mars as rather an ill-usedindividual. Very probably he was stationed somewhere in the vicinity,for loud appeals had been made for regular cavalry ever since the yearprevious, when the Ku-Klux began their devilment in the neighborhood.Very probably he knew Judge Summers; visited at his plantation; hadheard of Miss Kitty's coming, and was disposed to show her attention.Meeting her on the train alone and unescorted, he had done nothing morethan was right in offering his services. He had simply acted as agentleman, and been rebuffed. Ah, Miss Kitty, you must, indeed, be veryyoung, thought I, and so asked,--

"Have you been long in the South since the war, Miss Carrington?"

"I? Oh, no! We lived in Kentucky before the war, and when it broke outmother took me abroad. I was a little bit of a girl then, and was put atschool in Paris, but mother died very soon afterwards, and then auntietook charge of me. Why, I only left school last June!"

Poor little Kit! her father had died when she was a mere baby; hermother before the child had reached her tenth year; their beautiful oldhome in Kentucky had been sacked and burned during the war; and George,her only brother, after fighting for his "Lost Cause" until the lastshot was fired at Appomattox, had gone abroad, married, and settledthere. Much of the large fortune of their father still remained; andlittle Kit, now entering upon her eighteenth year, was the ward of JudgeSummers, her mother's brother, and quite an heiress.

All this I learned, partly at the time, principally afterwards from thejudge himself; but meantime there was the rebellious little fairy at myside with all the hatred and prejudice of ten years ago, little dreaminghow matters had changed since the surrender of her beloved Lee, orimagining the quantity of oil that had been poured forth upon thetroubled waters.

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier

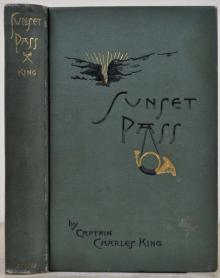

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land

Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days

From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days Annie o' the Banks o' Dee

Annie o' the Banks o' Dee The Black Sea

The Black Sea Under Fire

Under Fire Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier

Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War

Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68.

Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68. Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains A War-Time Wooing: A Story

A War-Time Wooing: A Story The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair

The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair Kitty's Conquest

Kitty's Conquest A Trooper Galahad

A Trooper Galahad Waring's Peril

Waring's Peril Marion's Faith.

Marion's Faith. Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila

Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul