- Home

- Charles King

The Black Sea Page 2

The Black Sea Read online

Page 2

Map 1. The Black Sea Today

Map 2. The Black Sea in Late Antiquity

Map 3. The Black Sea in the Middle Ages

Map 4. The Black Sea in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Whatever the Antients have said, the Black Sea has nothing Black in it, as I may say, beside the name.

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, royal botanist to Louis XIV, 1718

There’s not a sea the passenger e’er pukes in, Turns up more dangerous breakers than the Euxine.

Byron

The archaeologist’s spade delves into dwellings vacancied long ago

unearthing evidence of life-ways no one would dream of leading now, …

W. H. Audens

1

An Archaeology of Place

People and Water

There is a deep landlubber bias in historical and social research. History and social life, we seem to think, happen on the ground. What happens on the water—during a sea voyage or a cruise down a river, say—is just the scene-setter for the real action when the actors get where they are going. But oceans, seas, and rivers have a history of their own, not merely as highways or boundaries but as central players in distinct stories of human interaction and exchange. As Mark Twain wrote about the Mississippi, waterways have a physical history—of sediments and currents and floods—but they also have a “historical history”: of slumberous epochs and wide-awake ones, of the comings and goings of the characters who populate their shores.1 Shifting our geographical gaze from real estate to bodies of water can be illuminating. It forces us to think critically about such labels as “region” and “nation,” and the privileged role of these facile categories in how we carve up the world. It prompts a reexamination of the very meaning of place, how it changes over time, and how the intellectual lines that we draw around peoples and civilizations are far more capricious than might be imagined.

This book is about a sea and its role in the histories, cultures, and politics of the peoples and states around it. For some parts of the world, the idea of waterways as defining elements in human history is uncontroversial, even banal. We are accustomed to speaking about “the Mediterranean” as a meaningful place. As a modifier—Mediterranean cooking, a Mediterranean vacation—it conjures up an array of vivid images, of karst uplands and azure bays, of olives and wine and goats; as an object of research, it has been the focus of numerous scholarly studies, most famously Fernand Braudel’s portrait of the Mediterranean world at the dawn of modernity.2 Other bodies of water, both greater and lesser, have their own unique associations. Mention the South Pacific or the Chesapeake Bay, the Amazon or the Mississippi, and a host of images comes instantly to mind, some of them tourist-brochure fictions, others drawn from the real-life experiences of the people along the water’s edge. For these and other waterways, scholars have charted the common economic pursuits, styles of life, and political predicaments that have linked one coast with another, sometimes over great distances.3

Images and associations come less readily for the Black Sea. It is a body of water familiar to few people outside the region itself. For entire stretches of the Black Sea’s history, from its possible formation some seven or eight millennia ago to the political revolutions and environmental crisis of the late twentieth century, there are no more than a few specialist monographs to tell its story. Major powers—from Byzantium to the Ottomans to Russia—at various times had the sea at the center of their strategic aims, but there has been little research on the sea in the history of these empires. It is also a body of water that is situated at the intersection of several different academic specializations, and thus central to none of them. Especially in the United States, the cold war produced certain geographical prejudices that have proved to be very durable. By and large, research on domestic politics and international relations, and even history and culture, is conducted within the same regional limits as during the cold war. Specialists in one domain only rarely cross into the other.

For the areas around the Black Sea, the result has been a tradition of history-writing and social analysis that has apportioned the coastline to different realms. The modern history of the Balkans is usually seen either as an adjunct to the history of central Europe or as a congeries of disconnected, ethnonational histories. The Ukrainian and south Russian lands are treated separately from the Balkans, either as a part of Russian imperial history or, in the Ukrainian tradition, as a tragic story of delayed national liberation. The same goes for the Caucasus, both north and south. The Ottomans lurk in the wings and occasionally come onto the stage, but after the formation of the modern Turkish Republic the Turks disappear almost entirely from Europe, becoming instead a part of the study of the Middle East. The policies of grant-making bodies and government-sponsored research programs reinforce these lines, in the social sciences as well as the humanities. In the United States, research on “Eastern Europe” is funded through one budget line, work on “the former Soviet Union,” or something called the “New Independent States,” through another; research on the Middle East, including Turkey, is financed through yet another.

This mental map, however, is of distinctly modern vintage. Not all that long ago, the idea of the Black Sea as a kind of geopolitical unit would have made a great deal of sense, not only to local populations and political leaders, but also to Western diplomats, strategists, and writers who spent their careers dealing with the sea and its discontents. In the nineteenth century, the Black Sea lay at the heart of the Eastern Question, the complex rivalries associated with the weakening of the Ottoman empire and the interests of Europe’s great powers in how it would eventually be carved up. Between the two world wars, the area stood at the intersection of the turbulent Balkans, the Bolsheviks, and European protectorates in the Levant. Later, the countries of the region were on the front line in the global struggle between capitalism and communism, either as mavericks within the communist world, such as Albania, Yugoslavia, and Romania, or in the case of Greece and Turkey, as the vanguard of the West against the Soviet Union. Since the end of communism, southeastern Europe has become a region of troubled political transitions and relatively poor states, a worrying lacuna in Europe’s project of creating a united and prosperous continent. The disruption caused by weak states and collapsing regional orders, the spillover of domestic squabbles into international conflicts, and the politics of trade and energy networks were some of the main issues around the Black Sea before the Second World War. They are on the international agenda once again.

This book is an effort to bring together the histories, cultures, and politics of the peoples around the Black Sea and to recall an older intellectual map of Europe’s southeastern frontier. Apart from a relatively short time in the short twentieth century, Eastern Europe—at least the kind with two capital E’s—was not the way most people thought about the eastern extremity of the continent. That stretch of territory, from the Baltic to the Black Sea, did for a time have a common ideology, similar domestic political structures, and generally congruous foreign policies. But the farther we get from 1989, the less cosmically important that thing called communism (if it ever was just one thing) is likely to appear, especially for those countries that were part of the communist world for only a single generation and for their neighbors, such as Greece and Turkey, whose tastes in authoritarianism were not of the Marxist variety. The history of Europe’s east, in other words, is not the story of a place called Eastern Europe.4

In the 1990s, the idea of a homogeneous Eastern Europe was largely replaced by the notion of an equally heterogeneous southeastern Europe, a place at the timeless meeting place of mutually hostile religions and cultures, the transition zone between the real Europe and something else. Newspaper headlines seemed to provide ample proof: the bloody end of Yugoslavia; the wars of the Soviet succession, a series of small but vicious conflicts in Moldova, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and elsewhere; Turkey’s decades-long war with Kurdish guerrillas. There was surely something about the stre

ngth of communal belief or allegiance to kith and kin that made this region perpetually at odds with itself.

As the eminent American scholar and diplomat George Kennan wrote about the Balkans, the violence of the 1990s could best be explained by the “deeper traits of character inherited … from a distant tribal past” of which the people of the region were the unwitting victims.5

But over the long sweep of history, it is difficult to argue that the lands around the Black Sea—an area that might be called the wider southeastern Europe or, to use an antiquated term, the Near East—have been more volatile, a sense of ethnic identity more deeply felt, or questions of land, custom, and religion more divisive than in any other part of Europe or Eurasia. In many periods, in fact, they were a good deal less so. If there is an overarching story to the history of this sea, it is not about conflict and violence, least of all the kind that is said to define the fracture zones between incompatible “civilizations.” Rather, it is about the belated advent of the central organizing ideas of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Europe. It is a place to which the modern state came rather late, the culturally defined nation even later, and the nation-state even later still—not until the early twentieth century in some cases, not until the very end of that century in several others.

Much of the later parts of this book are about how the national idea came rushing into a world to which it had previously been alien, a world in which other poles of association such as occupation, religion or simple geography—being from the coast or the hinterland, from this village or that—normally held sway (and in which even these categories were rarely fixed). It is about how children came to define themselves in ways that would have seemed odd to their grandparents, and about how people whose identities were mixed and overlapping traded them in for homogeneous, national ones. This book also tells how a place that might once have existed as a meaningful geographic space was progressively unbuilt over the course of several centuries, how an array of human connections across a body of water rose and fell and rose again in tandem with changes in the political, economic, and strategic environment of Europe and Eurasia. It is an experiment in what might be called geographical archaeology. Its aim is to uncover a forgotten network of relationships, a filigree of human connections which, buried beneath the thin layers of communism and postcommunism, was in the latter half of the twentieth century hidden from view. At the center of this project lies the sea.

Region, Frontier, Nation

So far, I have been using some important terms rather cavalierly, so I should say something about what I mean by them and about their place in this book. One is “region.” Region, like culture and race, is a concept notoriously difficult to define—and a word whose analytical uses usually mask a multitude of normative connotations. No regional label can stand too much interrogation. As soon as one tries to identify an essential set of characteristics that is meant to distinguish some broad geographical unit from some other, those characteristics begin to look frustratingly ephemeral. At base, however, regions are not about commonalities of language, culture, religion or other traits that the constituents of the region—whether individuals, peoples or states—might share. Rather, they are about connections: profound and durable linkages among people and communities that seem to mark off one space from another.

This book is concerned with a region whose dimensions are admittedly vague. Peoples, empires, and countries enter and exit at different points, sometimes accompanied by another character, Europe, and sometimes spurned by her. But the center of the stage is the sea and its littoral; the wings extend from the Balkans to the Caucasus mountains and from the steppeland of Ukraine and southern Russia to central Anatolia. Conveniently, almost all the countries in this area are today members of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation organization (BSEC), an international forum established in 1992 to strengthen commercial, political, and cultural ties in southeastern Europe.

But is this place really a region? The answer depends on what spectacles we wear. In the narrowest geographical sense, only six countries can claim membership: Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Russia, Georgia, and Turkey. These states control the major port facilities and claim territorial waters off the coast. More broadly, however, a Black Sea region extends all the way from the Alps to the Urals, the entire swath of territory that constitutes the sea’s drainage basin, which covers all or part of some twenty-two countries. What happens upstream on the Danube, the Dnepr, and the Don rivers has a major impact on the health of the sea and the livelihoods of the populations around it. In terms of history, parts of the sea have sometimes been controlled by a major imperial power, but the coastline has most often been divided among many local rulers and modern states. In terms of recent politics, in the early 1990s the littoral countries and several of their neighbors committed themselves to building a regional cooperation organization, BSEC; but those aspirations have largely been overtaken by competition for the real prize of the early twenty-first century—membership in the European Union—a prize that some members of BSEC are far closer to attaining than others.

What constitutes a Black Sea region depends not only on how one asks the question but also on when it is asked. In the ancient world, a string of Greek cities and trading emporia connected all the corners of the sea into a single commercial network. That network was shaken by the rise of powers from the hinterlands and by the advance of Persia and Rome; relations among Byzantines, nomadic peoples in the north, and Christian kings and princes in the Balkans and the Caucasus at first strengthened and then weakened it. In the Middle Ages, the Black Sea world was revived by the entrepreneurial spirit of the Genoese and Venetians and, for a time, came under the sway of a single empire, even of a single man, the Ottoman sultan. Later, the rise of Russia transformed the sea into the site of a centuries-long struggle between the powers that controlled its northern and southern shores. In turn, the national movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, favoring smaller countries over empires, worked to bring bits of the sea and its littoral into the demesne of newly formed nation-states.

Today, it is difficult to argue that there is anything approaching a common Black Sea “regional identity” among all the inhabitants of the coasts or the states in which they live. Political trajectories and political realities across the wider southeastern Europe are varied: democratic and authoritarian, reformist and reactionary, real states and imagined ones. Political leaders are more likely to set themselves off from their neighbors—as more European, more deserving of membership in Euro-Atlantic institutions, or simply more civilized—than to engage in genuine regional cooperation. Still, the sea has long been a distinct place, a region defined by cross-sea relationships, both cooperative and conflictual, involving the movement of people, goods, and ideas. Over the long course of history, the communities around the coasts and in the hinterlands have touched one another in enduring ways. Religious practices, linguistic forms, musical and literary styles, folklore and foodways, among many other areas of social life, are joined together in a web of mutual influence that is readily apparent to even the most casual visitor—or at least to one who is able to look beyond the narratives of national uniqueness that, in the last century or so, have become dominant.

Another term that needs attention is “frontier.” Owen Lattimore, the historian of inner Asia, once noted that a frontier is not the same thing as a boundary.6 A boundary represents the intended limit of political power, the farthest extent to which a state or empire is able to exert its will on a geographical space. A frontier is the zone that exists on both sides of the boundary. It is a place inhabited by distinct communities of boundary-crossers, people whose lives and livelihoods depend on their being experts in transgressing both the physical boundaries between polities as well as the social ones between ethnic, religious, and linguistic groups. Frontier peoples—the Cossacks of Eurasia, the coureurs des bois of the Canadian forests, the mountain men of the American West, and many others like them—are not simply per

ipheral actors in human history but distinctive, highly adaptive cultures in their own right.

Attitudes toward these frontiers and their inhabitants can play a central role in the elaboration of imperial and national identities. The American historian Frederick Jackson Turner argued that the rolling conquest of the West shaped a unique American identity, a blend of European and indigenous traits forged in the harsh crucible of the frontier. “As successive terminal moraines result from successive glaciations,” Turner wrote in his famous essay on the frontier in American history, “so each frontier leaves its traces behind it, and when it becomes a settled area the region still partakes of frontier characteristics.”7 Turner was most concerned with the effect of natural challenges on social development, but he missed another crucial relationship. People shape themselves against the image of the frontier as much as, perhaps even more than, the frontier shapes them. As Lattimore’s work revealed, encounters with Turkicspeaking populations in Eurasia were central to Chinese understandings of civilization and proper conduct. Likewise, in nineteenth-century Russia, expansion and settlement in Siberia and the Caucasus were crucial components of both Russian imperial identity and the vision of Russia as a continental, Eurasian power. One can find the same dynamics at work as much on watery frontiers as on terrestrial ones.

At various points in history, the lands around the Black Sea have been frontiers in both these senses: the locus of distinct communities defined by their position between empires or states, and a foil against which the cultural and political identities of outsiders have been built. However, to think of the sea as a timeless frontier at the meeting place of different civilizational zones—Greek and barbarian, Christian and Muslim—or perhaps as part of a periphery of the imagination—Oriental, Balkan, Eurasian—against which Europeans have perpetually defined themselves, is to read back onto the distant past the prejudices of the present.

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier

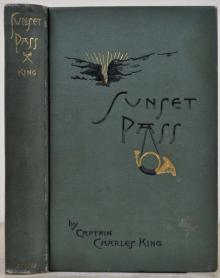

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land

Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days

From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days Annie o' the Banks o' Dee

Annie o' the Banks o' Dee The Black Sea

The Black Sea Under Fire

Under Fire Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier

Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War

Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68.

Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68. Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains A War-Time Wooing: A Story

A War-Time Wooing: A Story The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair

The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair Kitty's Conquest

Kitty's Conquest A Trooper Galahad

A Trooper Galahad Waring's Peril

Waring's Peril Marion's Faith.

Marion's Faith. Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila

Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul