- Home

- Charles King

A Trooper Galahad

A Trooper Galahad Read online

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Martin Pettit and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Thisfile was produced from images generously made availableby The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A TROOPER GALAHAD

BY CAPTAIN CHARLES KING, U.S.A.

AUTHOR OF "THE COLONEL'S DAUGHTER," "MARION'S FAITH," "CAPTAIN BLAKE,""UNDER FIRE," "FROM SCHOOL TO BATTLE-FIELD," ETC.

Logo]

PHILADELPHIAJ. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY1899

COPYRIGHT, 1898, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY.

ELECTROTYPED AND PRINTED BYJ. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY. PHILADELPHIA, U. S. A.

"Felling him like an ox. Page 107."]

* * * * *

BY CAPTAIN CHARLES KING, U.S.A.

BOOKS FOR BOYS.

TROOPER ROSS, AND SIGNAL BUTTE.FROM SCHOOL TO BATTLE-FIELD.

_8vo. Cloth, illustrated, $1.50._

NOVELS.

THE COLONEL'S DAUGHTER.CAPTAIN BLAKE.FOES IN AMBUSH (_Paper, 50 cents_).UNDER FIRE.MARION'S FAITH.THE GENERAL'S DOUBLE.

_12mo. Cloth, illustrated, $1.25._

TRIALS OF A STAFF OFFICER.WARING'S PERIL.A TROOPER GALAHAD.

_12mo. Cloth, $1.00._

KITTY'S CONQUEST.LARAMIE; OR, THE QUEEN OF BEDLAM.TWO SOLDIERS, AND DUNRAVEN RANCH.STARLIGHT RANCH, AND OTHER STORIES.THE DESERTER, AND FROM THE RANKS.A SOLDIER'S SECRET, AND AN ARMY PORTIA.CAPTAIN CLOSE, AND SERGEANT CROESUS.

_12mo. Cloth, $1.00; paper, 50 cents._

A TAME SURRENDER. A Story of the Chicago Strike.RAY'S RECRUIT.

_16mo. Polished buckram, illustrated, 75 cents.Issued in the Lotos Library._

Editor of THE COLONEL'S CHRISTMAS DINNER, AND OTHER STORIES.

_12mo. Cloth, $1.25; paper, 50 cents._

AN INITIAL EXPERIENCE, AND OTHER STORIES.CAPTAIN DREAMS, AND OTHER STORIES.

_12mo. Cloth, $1.00; paper, 50 cents._

* * * * *

A TROOPER GALAHAD

CHAPTER I.

"Life is full of ups and downs," mused the colonel, as he laid on thelittered desk before him an official communication just received fromDepartment Head-Quarters, "especially army life,--and more especiallyarmy life in Texas."

"Now, what are you philosophizing about?" asked his second in command, aburly major, glancing over the top of the latest home paper, three weeksold that day.

"D'ye remember Pigott, that little cad that was court-martialled at SanAntonio in '68 for quintuplicating his pay accounts? He married thewidow of old Alamo Hendrix that winter. He's worth half a millionto-day, is running for Congress, and will probably be on the militarycommittee next year, while here's Lawrence, who was judge advocate ofthe court that tried him, gone all to smash." And the veteran officercommanding the --th Infantry and the big post at Fort Worth glancedwarily along into the adjoining office, where a clerk was assorting thepapers on the adjutant's desk.

"It's the saddest case I ever heard of," said Major Brooks, tossingaside the _Toledo Blade_ and tripping up over his own, which he hadthoughtfully propped between his legs as he took his seat andthoughtlessly ignored as he left it. "Damn that sabre,--and the servicegenerally!" he growled, as he recovered his balance and tramped to thewindow. "I'd almost be willing to quit it as Pigott did if I could seemy way to a moderate competence anywhere out of it. Lawrence was as gooda soldier as we had in the 12th, and, yet, what can you do or say? Themischief's done." And, beating the devil's tattoo on the window, themajor stood gloomily gazing out over the parade.

"It isn't Lawrence himself I'm so---- Orderly, shut that door!" criedthe chief, whirling around in his chair, "and tell those clerks I wantit kept shut until the adjutant comes; and you stay out on theporch.--It isn't Lawrence I'm so sorely troubled about, Brooks. He hasability, and could pick up and do well eventually, but he's utterlydiscouraged and swamped. What's to become, though, of that poor childAda and his little boy?"

"God knows," said Brooks, sadly. "I've got five of my own to lookafter, and you've got four. No use talking of adopting them, even ifLawrence would listen; and he never would listen to anything oranybody--they tell me," he added, after a minute's reflection. "I don'tknow it myself. It's what Buxton and Canker and some of those fellowstold me on the Republican last summer. I hadn't seen him sinceGettysburg until we met here."

"Buxton and Canker be--exterminated!" said the colonel, hotly. "I nevermet Buxton, and never want to. As for Canker, by gad, there's anotherabsurdity. They put him in the cavalry because consolidation left noroom for him with us. What do you suppose they'll do with him in the--th?"

"The Lord knows, as I said before. He never rode anything but a hobby inhis life. I don't wonder Lawrence couldn't tolerate preaching from him.But what I don't understand is, who made the allegation. What's hisoffence? Every one knows that he's in debt and trouble, and that he'shad hard lines and nothing else ever since the war, but the courtacquitted him of all blame in that money business----"

"And now to make room for fellows with friends at court," burst in thecolonel, wrathfully, "he and other poor devils with nothing but afighting record and a family to provide for are turned loose on a year'spay, which they're to have after things straighten out as to theiraccounts with the government. Now just look at Lawrence! Ordnance andquartermaster's stores hopelessly boggled----"

"Hush!" interrupted Brooks, starting back from the window. "Here he isnow."

Assembly of the guard details had sounded a few moments before, and allover the sunshiny parade on its westward side, in front of the variousbarracks, little squads of soldiers armed and in full uniform werestanding awaiting the next signal, while the porches of the low woodenbuildings beyond were dotted with groups of comrades, lazily looking on.Out on the greensward, broad and level, crisscrossed with gravel walks,the band had taken its station, marshalled by the tall drum-major in hishuge bear-skin shako. From the lofty flag-staff in the centre of theparade the national colors were fluttering in the mountain breeze thatstole down from the snowy peaks hemming the view to the northwest andstirred the leaves of the cottonwoods and the drooping branches of thewillows in the bed of the rushing stream sweeping by the southern limitsof the garrison. Within the enclosure, sacred to military use, it wasall the same old familiar picture, the stereotyped fashion of thefrontier fort of the earliest '70s,--dull-hued barracks on one side oron two, dull-hued, broad-porched cottages--the officers' quarters--onanother, dull-hued offices, storehouses, corral walls, scattered aboutthe outskirts, a dull-hued, sombre earth on every side; sombre sweepingprairie beyond, spanned by pallid sky or snow-tipped mountains; atwisting, winding road or two, entering the post on one front, issuingat the other, and tapering off in sinuous curves until lost in thedistance; a few scattered ranches in the stream valley; a collection ofsheds, shanties, and hovels surrounding a bustling establishment knownas the store, down by the ford,--the centre of civilization, apparently,for thither trended every roadway, path, track, or trail visible to thenaked eye. Here in front of the office a solitary cavalry horse wastethered. Yonder at the sutler's, early as it was in the day, a dozenquadrupeds, mules, mustangs, or Indian ponies, were blinking in thesunshine. Dogs innumerable sprawled in the sand. Bipeds lolled lazilyabout or squatted on the steps on the edge of the wooden porch, some inbroad sombreros, some in scalp-lock and blanket,--none in the garb ofcivil life as seen in the nearest cities, and the nearest was four orfive hundred miles away. Out on the parade were bits of lively color,the dresses of frolicsome children to the east, the stripes and facingsof the cavalry and artillery at the west; for, by some odd freak of thefortunes of war, here, away out at Fort Worth, had come a crack lightbattery of the old army, which, with Brooks's battalion of the cavalry,and head-quarters' staff, band,

and six companies of the --th Infantry,made up the garrison,--the biggest then maintained in the Departmentimmortalized by Sheridan as only second choice to Sheol. It was thewinter of '70 and '71, as black and dreary a time as ever the army knew,for Congress had telescoped forty-five regiments into half the numberand blasted all hopes of promotion,--about the only thing the soldierhas to live for.

And that wasn't the blackest thing about the business, by any means. Thewar had developed the fact that we had thousands of battalion commandersfor whom the nation had no place in peace times, and scores of them, inthe hope and promise of a life employment in an honorable profession,accepted the tender of lieutenancies in the regular army in '66, the warhaving broken up all their vocations at home, and now, having given fouryears more to the military service,--taken all those years out of theirlives that might have been given to establishing themselves inbusiness,--they were bidden to choose between voluntarily quitting thearmy with a bonus of a year's pay, and remaining with no hope ofadvancement. Most of them, despairing of finding employment in civillife, concluded to stay: so other methods of getting rid of them weredevised, and, to the amaze of the army and the dismay of the victims, abig list was published of officers "rendered supernumerary" andsummarily discharged. And this was how it happened that a gallant,brilliant, and glad-hearted fellow, the favorite staff officer of aglorious corps commander who fell at the head of his men after threeyears of equally glorious service, found himself in far-away Texas thisblackest of black Fridays, suddenly turned loose on the world andwithout hope or home.

Cruel was no word for it. Entering the army before the war, one of thefew gifted civilians commissioned because they loved the service andthen had friends to back them, Edgar Lawrence had joined the cavalry inTexas, where the first thing he did was to fall heels over head in lovewith his captain's daughter, and a runaway match resulted. Poor KittyTyrrell! Poor Ned Lawrence! Two more unpractical people never lived. Shewas an army girl with aspirations, much sweetness, and little sense. Hewas a whole-souled, generous, lavish fellow. Both were extravagant, sheparticularly so. They were sorely in debt when the war broke out, andhe, instead of going in for the volunteers, was induced to becomeaide-de-camp to his old colonel, who passed him on to another when heretired; and when the war was half over Lawrence was only a captain ofstaff, and captain he came out at the close. Brevets of course he had,but what are brevets but empty title? What profiteth it a man to becalled colonel if he have only the pay of a sub? Hundreds of men whoeagerly sought his aid or influence during the war "held over him" atthe end of it. Another general took him on his staff as aide-de-camp,where Lawrence was invaluable. Kitty dearly loved city life, parties,balls, operas, and theatres; but Lawrence grew lined and gray with careand worry. The general went the way of all flesh, and Lawrence to Texas,unable to get another staff billet. They set him at court-martial dutyat San Antonio for several months, for Texas furnished culprits by thescore in the days that followed the war, and many an unpromising armycareer was cut short by the tribunal of which Captain and BrevetLieutenant-Colonel Lawrence was judge advocate; but all the time he hada skeleton in his own closet that by and by rattled its way out. Timewas in the war days when many of the men of the head-quarters escortbanked their money with the beloved and popular aide. He had nearlytwelve hundred dollars when the long columns probed the Wilderness in'64. It was still with him when he was suddenly sent back to Washingtonwith the body of his beloved chief, but every cent was gone before hegot there, stolen from him on the steamer from Acquia Creek, and never atrace was found of it thereafter. For years he was paying that off,making it good in driblets, but while he was serving faithfully inTexas, commanding a scout that took him miles and miles away over theLlano Estacado, there were inimical souls who worked the story of hisindebtedness to enlisted men for all it was worth, and, aided by thecomplaints of some of their number, to his grievous disadvantage. Hecame home from a brilliant dash after the Kiowas to find himselfcomplimented in orders and confronted by charges in one and the samebreath. The court acquitted him of the charges and "cut" his accusers,but the shame and humiliation of it all seemed to prey upon his spirits;and then Kitty Tyrrell died.

"If that had only happened years before," said the colonel, "it wouldhave been far better for Lawrence, for she conscientiously believedherself the best wife in the world, and spent every cent of his incomein dressing up to her conception of the character." Once the mostdashing and debonair of captains, poor Ned ran down at the heel andseemed unable to rally. New commanders came to the department, to hisregiment, and new officials to the War Office,--men "who knew notJoseph;" and when the drag-net was cast into the whirlpool of army namesand army reputations, it was set for scandal, not for services, and theold story of those unpaid hundreds was enmeshed and served up seasonedwith the latest spice obtainable from the dealers rebuked of thatoriginal court. And, lo! when the list of victims reached Fort Worth inthe reorganization days, old Frazier, the colonel, burst into a stringof anathemas, and more than one good woman into a passion of tears, forpoor Ned Lawrence, at that moment long days' marches away towards theRio Bravo, was declared supernumerary and mustered out of the service ofthe United States with one year's pay,--pay which he could not hope toget until every government account was satisfactorily straightened, andthis, too, at a time when the desertion of one sergeant and the death ofanother revealed the fact that his storehouses had been systematicallyrobbed and that he was hopelessly short in many a costly item chargedagainst him. That heartless order was a month old when the strickensoldier reached his post, and then and there for the first time learnedhis fate.

Yes, they had tried to break it to him. Letters full of sympathy werewritten and sent by couriers far to the north; others took them on theConcho trail. Brooks and Frazier both wrote to San Antonio messagesthence to be wired to Washington imploring reconsideration; but the deedwas done. Astute advisers of the War Secretary clinched the matter bythe prompt renomination of others to fill the vacancies just created,and once these were confirmed by the Senate there could be no appeal.The detachment led by Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel Lawrence, so later saidthe Texas papers, had covered itself with glory, but in its pursuit ofthe fleeing Indians it had gone far to the northeast and so came home bya route no man had dreamed of, and Lawrence, spurring eagerly ahead,rode in at night to fold his motherless little ones to his heart, andfound loving army women aiding their faithful old nurse in ministeringto them, but read disaster in the tearful eyes and faltering words thatwelcomed him.

Then he was ill a fortnight, and then he had to go. He could not, wouldnot believe the order final. He clung to the hope that he would find atWashington a dozen men who knew his war record, who could remember hisgallant services in a dozen battles, his popularity and prominence inthe Army of the Potomac. Everybody knows the favorite aide-de-camp of acorps commander when colonels go begging for recognition, and everybodyhas a cheery, cordial word for him so long as he and his general liveand serve together. But that proves nothing when the general is gone.Colonels who eagerly welcomed and shook hands with the aide-de-camp andtalked confidentially with him about other colonels in days when he rodelong hours by his general's side, later passed him by with scant notice,and "always thought him a much overrated man." Right here at Fort Worthwere fellows who, six or seven years before, would have given a month'spay to win Ned Lawrence's influence in their behalf,--for, like"Perfect" Bliss of the Mexican war days, Lawrence was believed to writehis general's despatches and reports,--but who now shrank uneasily outof his way for fear that he should ask a favor.

Even Brooks, who liked and had spoken for him, drew back from the windowwhen with slow, heavy steps the sad-faced, haggard man came slowly alongthe porch. The orderly sprang up and stood at salute just as adjutant'scall sounded, and the band pealed forth its merry, spirited music. Fora moment the new-comer turned and glanced back over the parade, nowdotted with little details all marching out to the line where stood thesergeant-major; then he turned, entered the

building, and paused withhopeless eyes and pallid, careworn features at the office doorway. Hisold single-breasted captain's frock-coat, with its tarnished silverleaves at the shoulders, hung loosely about his shrunken form. Thetrousers, with their narrow welt of yellow at the seam, looked far toobig for him. His forage-cap, still natty in shape, was old and worn. Hischin and cheeks bristled with a stubbly grayish beard. All the old alertmanner was gone. The once bright eyes were bleary and dull. Neighborssaid that poor Ned had been drinking deep of the contents of a demijohna sympathetic soul had sent him, and half an eye could tell that his lipwas tremulous. The colonel arose and held out his hand.

"Come in, Lawrence, old fellow, and tell me what I can do for you." Hespoke kindly, and Brooks, too, turned towards the desolate man.

"You've done--all you could--both of you. God bless you!" was thefaltering answer. "I've come to say I start at once. I'm going right toWashington to have this straightened out. I want to thank you, colonel,and you too, Brooks, for all your willing help. I'll try to show myappreciation of it when I get back."

"But Ada and little Jim, Lawrence; surely they're not ready for thatlong journey yet," said Frazier, thinking sorrowfully of what his wifehad told him only the day before,--that they had no decent winterclothing to their names.

"It's all right. Old Mammy stays right here with them. She has takencare of them, you know, ever since my poor wife died. I can keep my oldquarters a month, can't I?" he queried, with a quivering smile. "Even ifthe order isn't revoked, it would be a month or more before any onecould come to take my place. Mrs. Blythe will look after the childrenday and night."

Frazier turned appealingly to Brooks, who shook his head and refused tospeak, and so the colonel had to.

"Lawrence, God knows I hate to say one word of discouragement, but Ifear--I fear you'd better wait till next week's stage and take thosepoor little folks with you. I've watched this thing. I know how a dozengood fellows, confident as yourself, have gone on to Washington andfound it all useless."

"It can't be useless, sir," burst in the captain, impetuously. "Truth istruth and must prevail. If after all my years of service I can find nofriends in the War Office, then life is a lie and a sham. Senator Hallwrites me that he will leave no stone unturned. No, colonel, I take thestage at noon to-day. Will you let Winn ride with me as far as CastlePeak? I've got to run down and see Fuller now."

"Winn can go with you, certainly; but indeed, Lawrence, I shall have tosee you again about this."

"I'll stop on the way back," said Lawrence, nervously. "Fuller promisedto see me before he went out to his ranch." And hastily the captainturned away.

For a moment the two seniors stood there silently gazing into eachother's eyes. "What can one do or say?" asked the colonel, at last. "Isuppose Fuller is going to let him have money for the trip. He canafford to, God knows, after all he's made out of this garrison. But thequestion is, ought I not to make poor Lawrence understand that it's agone case? He is legally out already. His successor is on his way here.I got the letter this morning."

"On his way here? Who is he?" queried the major, in sudden interest."They didn't know when Stone came through San Antonio ten days ago."

"Man named Barclay; just got his captaincy in the 30th,--but wasconsolidated out of that, of course."

"Barclay--Barclay, you say?" ejaculated the major, in excitement. "Well,of all the----"

"Of all the what?" demanded the colonel, impatiently. "Nothing wrongwith him, I hope."

"Wrong? No, or they wouldn't have dubbed him Galahad. But, talk aboutups and downs in Texas, this beats all. Does Winn know?"

"I don't know that any one knows but you and me," answered the veteran,half testily. "What's amiss? What has Winn to do with it?"

"Blood and blue blazes! Why, of course you couldn't know. Three yearsago Barclay believed himself engaged to a girl, and she threw him overfor Winn, and now we'll have all three of them right here at Worth."

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier

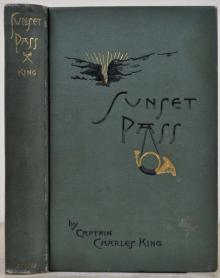

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land

Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days

From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days Annie o' the Banks o' Dee

Annie o' the Banks o' Dee The Black Sea

The Black Sea Under Fire

Under Fire Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier

Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War

Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68.

Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68. Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains A War-Time Wooing: A Story

A War-Time Wooing: A Story The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair

The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair Kitty's Conquest

Kitty's Conquest A Trooper Galahad

A Trooper Galahad Waring's Peril

Waring's Peril Marion's Faith.

Marion's Faith. Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila

Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul