- Home

- Charles King

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Page 5

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Read online

Page 5

CHAPTER V

THE CAPTAIN'S DEFIANCE

Within ten minutes of Todd's arrival at the spot the soft sands of the_mesa_ were tramped into bewildering confusion by dozens of trooperboots. The muffled sound of excited voices, so soon after thestartling affair of the earlier evening, and hurrying footfallsfollowing, had roused almost every household along the row and broughtto the spot half the officers on duty at the post. A patrol of theguard had come in double time, and soldiers had been sent at speed tothe hospital for a stretcher. Dr. Graham had lost no moment of time inreaching the stricken sentry. Todd had been sent back to Blakely'sbedside and Downs to fetch a lantern. They found the latter, fiveminutes later, stumbling about the Trumans' kitchen, weeping for thatwhich was lost, and the sergeant of the guard collared and cuffed himover to the guard-house--one witness, at least, out of the way. Atfour o'clock the doctor was working over his exhausted and unconsciouspatient at the hospital. Mullins had been stabbed twice, anddangerously, and half a dozen men with lanterns were hunting about thebloody sands where the faithful fellow had dropped, looking for aweapon or a clew, and probably trampling out all possibility offinding either. Major Plume, through Mr. Doty, his adjutant, had feltit necessary to remind Captain Wren that an officer in close arresthad no right to be away from his quarters. Late in the evening, itseems, Dr. Graham had represented to the post commander that thecaptain was in so nervous and overwrought a condition, and sodistressed, that as a physician he recommended his patient be allowedthe limits of the space adjoining his quarters in which to walk offhis superabundant excitement. Graham had long been the friend ofCaptain Wren and was his friend as well as physician now, even thoughdeploring his astounding outbreak, but Graham had other things todemand his attention as night wore on, and there was no one to speakfor Wren when the young adjutant, a subaltern of infantry, withunnecessary significance of tone and manner, suggested the captain'simmediate return to his proper quarters. Wren bowed his head and wentin stunned and stubborn silence. It had never occurred to him for amoment, when he heard that half-stifled, agonized cry for help, thatthere could be the faintest criticism of his rushing to the sentry'said. Still less had it occurred to him that other significance, anddamning significance, might attach to his presence on the spot, but,being first to reach the fallen man, he was found kneeling over himwithin thirty seconds of the alarm. Not another living creature was insight when the first witnesses came running to the spot. Both Trumanand Todd could swear to that.

In the morning, therefore, the orderly came with the customarycompliments to say to Captain Wren that the post commander desired tosee him at the office.

It was then nearly nine o'clock. Wren had had a sleepless night andwas in consultation with Dr. Graham when the summons came. "Ask thatCaptain Sanders be sent for at once," said the surgeon, as he pressedhis comrade patient's hand. "The major has his adjutant and clerk andpossibly some other officers. You should have at least one friend."

"I understand," briefly answered Wren, as he stepped to the hallway toget his sun hat. "I wish it might be you." The orderly was alreadyspeeding back to the office at the south end of the brown rectangle ofadobe and painted pine, but Janet Wren, ministering, according to herlights, to Angela in the little room aloft, had heard the message andwas coming down. Taller and more angular than ever she looked as, withflowing gown, she slowly descended the narrow stairway.

"I have just succeeded in getting her to sleep," she murmured. "Shehas been dreadfully agitated ever since awakened by the voices and therunning this morning, and she must have cried herself to sleep lastnight. R-r-r-obert, would it not be well for you to see her when shewakes? She does not know--I could not tell her--that you are underarrest."

Graham looked more "dour" than did his friend of the line. Privatelyhe was wondering how poor Angela could get to sleep at all with AuntJanet there to soothe her. The worst time to teach a moral lesson,with any hope of good effect, is when the recipient is suffering fromsense of utter injustice and wrong, yet must perforce listen. But itis a favorite occasion with the "ower guid." Janet thought it would bea long step in the right direction to bring her headstrong niece tothe belief that all the trouble was the direct result of her havingsought, against her father's wishes, a meeting with Mr. Blakely. True,Janet had now some doubt that such had been the case, but, in what shefelt was only stubborn pride, her niece refused all explanation."Father would not hear me at the time," she sobbed. "I am condemnedwithout a chance to defend myself or--him." Yet Janet loved the bonnychild devotedly and would go through fire and water to serve her bestinterests, only those best interests must be as Janet saw them. Thatanything very serious might result as a consequence of her brother'sviolent assault on Blakely, she had never yet imagined. That furthercomplications had arisen which might blacken his record she nevercould credit for a moment. Mullins lay still unconscious, and notuntil he recovered strength was he to talk with or see anyone. Grahamhad given faint hope of recovery, and declared that everythingdepended on his patient's having no serious fever or setback. In a fewdays he might be able to tell his story. Then the mystery as to hisassailant would be cleared in a breath. Janet had taken deep offensethat the commanding officer should have sent her brother into closearrest without first hearing of the extreme provocation. "It is anutterly unheard-of proceeding," said she, "this confining of anofficer and gentleman without investigation of the affair," and sheglared at Graham, uncomprehending, when, with impatient shrug of hisbig shoulders, he asked her what had they done, between them, toAngela. It was his wife put him up to saying that, she reasoned, forJanet's Calvinistic dogmas as to daughters in their teens were ever atvariance with the views of her gentle neighbor. If Angela had beenharshly dealt with, undeserving, it was Angela's duty to say so and tosay why, said Janet. Meantime, her first care was her wronged andmisjudged brother. Gladly would she have gone to the office with himand stood proudly by his side in presence of his oppressor, could sucha thing be permitted. She marveled that Robert should now show solittle of tenderness for her who had served him loyally, ifmasterfully, so very long. He merely laid his hand on hers and said hehad been summoned to the commanding officer's, then went forth intothe light and left her.

Major Plume was seated at his desk, thoughtful and perplexed. Up atregimental headquarters at Prescott Wren was held in high esteem, andthe major's brief telegraphic message had called forth anxious inquiryand something akin to veiled disapprobation. Headquarters could notsee how it was possible for Wren to assault Lieutenant Blakely withoutsome grave reason. Had Plume investigated? No, but that was comingnow, he said to himself, as Wren entered and stood in silence beforehim.

The little office had barely room for the desks of the commander andhis adjutant and the table on which were spread the files of generalorders from various superior headquarters--regimental, department,division, the army, and the War Secretary. No curtains adorned thelittle windows, front and rear. No rug or carpet vexed the warpingfloor. Three chairs, kitchen pattern, stood against the pine partitionthat shut off the sight, but by no means the hearing, of the threeclerks scratching at their flat-topped desks in the adjoining den.Maps of the United States, of the Military Division of the Pacific,and of the Territory, as far as known and surveyed, hung about thewooden walls. Blue-prints and photographs of scout maps, made by theirpredecessors of the ----th Cavalry in the days of the Crook campaigns,were scattered with the order files about the table. But of pictures,ornamentation, or relief of any kind the gloomy box was destitute asthe dun-colored flat of the parade. Official severity spoke in everyfeature of the forbidding office as well as in those of the majorcommanding.

There was striking contrast, too, between the man at the desk and theman on the rack before him. Plume had led a life devoid of anxiety orcare. Soldiering he took serenely. He liked it, so long as no gravehardship threatened. He had done reasonably good service at corpsheadquarters during the Civil War; had been commissioned captain inthe regulars in '61, and held no vexatious command at a

ny timeperhaps, until this that took him to far-away Arizona. Plume was agentlemanly fellow and no bad garrison soldier. He really shone onparade and review at such fine stations as Leavenworth and Riley, buthad never had to bother with mountain scouting or long-distance Indianchasing on the plains. He had a comfortable income outside his pay,and when he was wedded, at the end of her fourth season in society, toa prominent, if just a trifle _passee_ belle, people thought him amore than lucky man, until the regiment was sent to Arizona and he toSandy. Gossip said he went to General Sherman with appeal for somedetaining duty, whereupon that bluff and most outspoken warriorexclaimed: "What, what, what! Not want to go with the regiment? Why,here's Blakely begging to be relieved from Terry's staff because he'smad to go." And this, said certain St. Louis commentators, settled it,for Mrs. Plume declared for Arizona.

Well garbed, groomed, and fed was Plume, a handsome, soldierly figure.Very cool and placid was his look in the spotless white that even thenby local custom had become official dress for Sandy; but beneath thesnowy surface his heart beat with grave disquiet as he studied thestrong, rugged, somber face of the soldier on the floor.

Wren was tall and gaunt and growing gray. His face was deeply lined;his close-cropped beard was silver-stranded; his arms and legs werelong and sinewy and powerful; his chest and shoulders burly; hisregimental dress had not the cut and finish of the commander's. Toomuch of bony wrist and hand was in evidence, too little of grace andcurve. But, though he stood rigidly at attention, with all semblanceof respect and subordination, the gleam in his deep-set eyes, thetwitch of the long fingers, told of keen and pent-up feeling, and helooked the senior soldier squarely in the face. A sergeant, standingby the adjutant's desk, tiptoed out into the clerk's room and closedthe door behind him, then set himself to listen. Young Doty, theadjutant, fiddled nervously with his pen and tried to go on signingpapers, but failed. It was for Plume to break the awkward silence, andhe did not quite know how. Captain Westervelt, quietly entering at themoment, bowed to the major and took a chair. He had evidently beensent for.

"Captain Wren," presently said Plume, his fingers trembling a bit asthey played with the paper folder, "I have felt constrained to sendfor you to inquire still further into last night's affair--or affairs.I need not tell you that you may decline to answer if you consideryour interests are--involved. I had hoped this painful matter might beso explained as to--as to obviate the necessity of extreme measures,but your second appearance close to Mr. Blakely's quarters, under allthe circumstances, was so--so extraordinary that I am compelled tocall for explanation, if you have one you care to offer."

For a moment Wren stood staring at his commander in amaze. He hadexpected to be offered opportunity to state the circumstances leadingto his now deeply deplored attack on Mr. Blakely, and to decline theoffer on the ground that he should have been given that opportunitybefore being submitted to the humiliation of arrest. He had intendedto refuse all overtures, to invite trial by court-martial orinvestigation by the inspector general, but by no manner of means toplead for reconsideration now; and here was the post commander, withwhom he had never served until they came to Sandy, a man who hadn'tbegun to see the service, the battles, and campaigns that had fallento his lot, virtually accusing him of further misdemeanor, when he hadonly rushed to save or succor. He forgot all about Sanders or otherwitnesses. He burst forth impetuously:

"Extraordinary, sir! It would have been most extraordinary if I hadn'tgone with all speed when I heard that cry for help."

Plume looked up in sudden joy. "You mean to tell me you didn't--youweren't there till after--the cry?"

Wren's stern Scottish face was a sight to see. "Of what can youpossibly be thinking, Major Plume?" he demanded, slowly now, for wrathwas burning within him, and yet he strove for self-control. He had hada lesson and a sore one.

"I will answer that--a little later, Captain Wren," said Plume, risingfrom his seat, rejoicing in the new light now breaking upon him.Westervelt, too, had gasped a sigh of relief. No man had ever knownWren to swerve a hair's breadth from the truth. "At this moment timeis precious if the real criminal is to be caught at all. You werefirst to reach the sentry. Had you seen no one else?"

In the dead silence that ensued within the room the sputter of hoofswithout broke harshly on the ear. Then came spurred boot heels on thehollow, heat-dried boarding, but not a sound from the lips of CaptainWren. The rugged face, twitching with pent-up indignation the momentbefore, was now slowly turning gray. Plume stood facing him in growingwonder and new suspicion.

"You heard me, did you not? I asked you did you see anyone elseduring--along the sentry post when you went out?"

A fringed gauntlet reached in at the doorway and tapped. SergeantShannon, straight as a pine, stood expectant of summons to enter andhis face spoke eloquently of important tidings, but the major wavedhim away, and, marveling, he slowly backed to the edge of the porch.

"Surely you can answer that, Captain Wren," said Plume, his clear-cut,handsome face filled with mingled anxiety and annoy. "Surely you_should_ answer, or--"

The ellipsis was suggestive, but impotent. After a painful moment camethe response:

"Or--take the consequences, major?" Then slowly--"Very well, sir--Imust take them."

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier

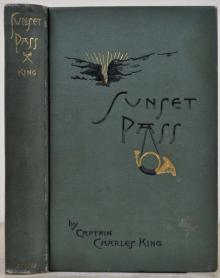

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land

Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days

From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days Annie o' the Banks o' Dee

Annie o' the Banks o' Dee The Black Sea

The Black Sea Under Fire

Under Fire Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier

Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War

Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68.

Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68. Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains A War-Time Wooing: A Story

A War-Time Wooing: A Story The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair

The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair Kitty's Conquest

Kitty's Conquest A Trooper Galahad

A Trooper Galahad Waring's Peril

Waring's Peril Marion's Faith.

Marion's Faith. Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila

Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul