- Home

- Charles King

Waring's Peril Page 5

Waring's Peril Read online

Page 5

CHAPTER V.

All that day the storm raged in fury; the levee road was blocked inplaces by the boughs torn from overhanging trees, and here, there, andeverywhere turned into a quagmire by the torrents that could find noadequate egress to the northward swamps. For over a mile above thebarracks it looked like one vast canal, and by nine o'clock it wasutterly impassable. No cars were running on the dilapidated road to the"half-way house," whatever they might be doing beyond. There was onlyone means of communication between the garrison and the town, and that,on horseback along the crest of the levee, and people in thesecond-story windows of the store- and dwelling-houses along theother side of the way, driven aloft by the drenched condition of theground floor, were surprised to see the number of times some Yankeesoldier or other made the dismal trip. Cram, with a party of four, wasperhaps the first. Before the dripping sentries of the old guard wererelieved at nine o'clock every man and woman at the barracks was awarethat foul murder had been done during the night, and that old Lascelles,slain by some unknown hand, slashed and hacked in a dozen places,according to the stories afloat, lay in his gloomy old library up thelevee road, with a flood already a foot deep wiping out from the groundsabout the house all traces of his assailants. Dr. Denslow, in examiningthe body, found just one deep, downward stab, entering above the upperrib and doubtless reaching the heart,--a stab made by a long, straight,sharp, two-edged blade. He had been dead evidently some hours whendiscovered by Cram, who had now gone to town to warn the authorities,old Brax meantime having taken upon himself the responsibility ofplacing a guard at the house, with orders to keep Alphonse and hismother in and everybody else out.

It is hardly worth while to waste time on the various theories advancedin the garrison as to the cause and means of the dreadful climax. ThatDoyle should be away from the post provoked neither comment norspeculation: he was not connected in any way with the tragedy. But thefact that Mr. Waring was absent all night, coupled with the stories ofhis devotions to Madame, was to several minds _prima facie_ evidencethat his was the bloody hand that wrought the deed,--that he was now afugitive from justice, and Madame Lascelles, beyond doubt, the guiltypartner of his flight. Everybody knew by this time of their beingtogether much of the morning: how could people help knowing, when Drydenhad seen them? In his elegantly jocular way, Dryden was alreadycondoling with Ferry on the probable loss of his Hatfield clothes, andcomforting him with the assurance that they always gave a feller a newblack suit to be hanged in, so he might get his duds back after all,only they must get Waring first. Jeffers doubtless would have beenbesieged with questions but for Cram's foresight: his master had orderedhim to accompany him to town.

In silence a second time the little party rode away, passing the floodedhomestead where lay the murdered man, then, farther on, gazing in mutecuriosity at the closed shutters of the premises some infantry satiristshad already christened "the dove-cot." What cared they for him or hisobjectionable helpmate? Still, they could not but note how gloomy anddeserted it all appeared, with two feet of water lapping the gardenwall. Summoned by his master, Jeffers knuckled his oil-skin hat-brim andpointed out the spot where Mr. Waring stood when he knocked the cabmaninto the mud, but Jeffers's tongue was tied and his cockney volubilitygone. The tracks made by Cram's wagon up the slope were already washedout. Bending forward to dodge the blinding storm, the party pushed alongthe embankment until at last the avenues and alleys to their right gaveproof of better drainage. At Rampart Street they separated, Pierce goingon to report the tragedy to the police, Cram turning to his right andfollowing the broad thoroughfare another mile, until Jeffers, indicatinga big, old-fashioned, broad-galleried Southern house standing in themidst of grounds once trim and handsome, but now showing signs ofneglect and penury, simply said, "'Ere, sir." And here the partydismounted.

Cram entered the gate and pulled a clanging bell. The door was almostinstantly opened by a colored girl, at whose side, with eager joyousface, was the pretty child he had seen so often playing about theLascelles homestead, and the eager joyous look faded instantly away.

"She t'ink it M'sieur Vareeng who comes to arrive," explained thesmiling colored girl.

"Ah! It is Madame d'Hervilly I wish to see," answered Cram, briefly."Please take her my card." And, throwing off his dripping raincoat andtossing it to Jeffers, who had followed to the veranda, the captainstepped within the hall and held forth his hands to Nin Nin, begging herto come to him who was so good a friend of Mr. Waring. But she wouldnot. The tears of disappointment were in the dark eyes as the little oneturned and ran away. Cram could hear the gentle, soothing tones of themother striving to console her child,--the one widowed and the otherorphaned by the tidings he bore. Even then he noted how musical, howfull of rich melody, was that soft Creole voice. And then Madamed'Hervilly appeared, a stately, dignified, picturesque gentlewoman ofperhaps fifty years. She greeted him with punctilious civility, but withmanner as distant as her words were few.

"I have come on a trying errand," he began, when she held up a slender,jewelled hand.

"_Pardon. Permettez._--Madame Lascelles," she called, and before Cramcould find words to interpose, a servant was speeding to summon the verywoman he had hoped not to have to see.

"Oh, madame," he murmured low, hurriedly, "I deplore my ignorance. Icannot speak French. Try to understand me. Mr. Lascelles is home,dangerously stricken. I fear the worst. You must tell her."

"'Ome! _La bas? C'est impossible._"

"It is true," he burst in, for the swish of silken skirt was heard downthe long passage. "_Il est mort_,--_mort_" he whispered, mustering upwhat little French he knew and then cursing himself for an imbecile.

"_Mort! O ciel!_" The words came with a shriek of anguish from the lipsof the elder woman and were echoed by a scream from beyond. In aninstant, wild-eyed, horror-stricken, Emilie Lascelles had sprung to hertottering mother's side.

"When? What mean you?" she gasped.

"Madame Lascelles," he sadly spoke, "I had hoped to spare you this, butit is too late now. Mr. Lascelles was found lying on the sofa in hislibrary this morning. He had died hours before, during the night."

And then he had to spring and catch the fainting woman in his arms. Shewas still moaning, and only semi-conscious, when the old family doctorand her brother, Pierre d'Hervilly, arrived.

Half an hour later Cram astonished the aides-de-camp and other boredstaff officials by appearing at the general loafing-room athead-quarters. To the chorus of inquiry as to what brought him up insuch a storm he made brief reply, and then asked immediately to speakwith the adjutant-general and Lieutenant Reynolds, and, to the disgustand mystification of all the others, he disappeared with these into anadjoining room. There he briefly told the former of the murder, and thenasked for a word with the junior.

Reynolds was a character. Tall, handsome, and distinguished, he hadserved throughout the war as a volunteer, doing no end of good work, andgetting many a word of praise, but, as all his service was as a staffofficer, it was his general who reaped the reward of his labors. He hadrisen, of course, to the rank of major in the staff in the volunteers,and everybody had prophesied that he would be appointed a major in theadjutant- or inspector-general's department in the permanentestablishment. But there were not enough places by any means, and thefew vacancies went to men who knew better how to work for themselves."Take a lieutenancy now, and we will fix you by and by," was thesuggestion, and so it resulted that here he was three years after thewar wearing the modest strap of a second lieutenant, doing the dutiesand accepting the responsibilities of a far higher grade, and beingpatronized by seniors who were as much his inferiors in rank as theywere in ability during the war days. Everybody said it was a shame, andnobody helped to better his lot. He was a man whose counsel was valuableon all manner of subjects. Among other things, he was well versed in allthat pertained to the code of honor as it existed in the antebellumdays,--had himself been "out," and, as was well known, had but recentlyofficiated as second for an officer who

had need of his services. He andWaring were friends from the start, and Cram counted on tidings of hisabsent subaltern in appealing to him. Great, therefore, was hisconsternation when in reply to his inquiry Reynolds promptly answeredthat he had neither seen nor heard from Waring in over forty-eighthours. This was a facer.

"What's wrong, Cram?"

"Read that," said the captain, placing a daintily-written note in theaide-de-camp's hand. It was brief, but explicit:

"COLONEL BRAXTON: Twice have I warned you that the attentions of yourLieutenant Waring to Madame Lascelles meant mischief. This morning,under pretence of visiting her mother, she left the house in a cab, butin half an hour was seen driving with Mr. Waring. This has been, as Ihave reason to know, promptly carried to Monsieur Lascelles by peoplewhom he had employed for the purpose. I could of told you last nightthat Monsieur Lascelles's friend had notified Lieutenant Waring that aduel would be exacted should he be seen with Madame again, and now itwill certainly come. You have seen fit to scorn my warnings hitherto,the result is on your head." There was no signature whatever.

"Who wrote this rot?" asked Reynolds. "It seems to me I've seen thathand before."

"So have I, and pitched the trash into the fire, as I do everythinganonymous that comes my way. But Brax says that this is the second orthird, and he's worried about it, and thinks there may be truth in thestory."

"As to the duel, or as to the devotions to Madame?" asked Reynolds,calmly.

"We-ll, both, and we thought you would be most apt to know whether afight was on. Waring promised to return to the post at taps last night.Instead of that, he is gone,--God knows where,--and the old man, thereputed challenger, lies dead at his home. Isn't that ugly?"

Reynolds's face grew very grave.

"Who last saw Waring, that you know of?"

"My man Jeffers left him on Canal Street just after dark last night. Hewas then going to dine with friends at the St. Charles."

"The Allertons?"

"Yes."

"Then wait till I see the chief, and I'll go with you. Say nothing aboutthis matter yet."

Reynolds was gone but a moment. A little later Cram and the aide were atthe St. Charles rotunda, their cards sent up to the Allertons' rooms.Presently down came the bell-boy. Would the gentleman walk up to theparlor? This was awkward. They wanted to see Allerton himself, and Cramfelt morally confident that Miss Flora Gwendolen would be on hand towelcome and chat with so distinguished a looking fellow as Reynolds.There was no help for it, however. It would be possible to draw off thehead of the family after a brief call upon the ladies. Just as they wereleaving the marble-floored rotunda, a short, swarthy man in"pepper-and-salt" business suit touched Cram on the arm, begged a word,and handed him a card.

"A detective,--already?" asked Cram, in surprise.

"I was with the chief when Lieutenant Pierce came in to report thematter," was the brief response, "and I came here to see your man. He isreluctant to tell what he knows without your consent. Could you have himleave the horses with your orderly below and come up here a moment?"

"Why, certainly, if you wish; but I can't see why," said Cram,surprised.

"You will see, sir, in a moment."

And then Jeffers, with white, troubled face, appeared, and twisted hiswet hat-brim in nervous worriment.

"Now what do you want of him?" asked Cram.

"Ask him, sir, who was the man who slipped a greenback into his hand atthe ladies' entrance last evening. What did he want of him?"

Jeffers turned a greenish yellow. His every impulse was to lie, and thedetective saw it.

"You need not lie, Jeffers," he said, very quietly. "It will do no good.I saw the men. I can tell your master who one of them was, and possiblylay my hands on the second when he is wanted; but I want you to tell andto explain what that greenback meant."

Then Jeffers broke down and merely blubbered.

"Hi meant no 'arm, sir. Hi never dreamed there was hanythink wrong.'Twas Mr. Lascelles, sir. 'E said 'e came to thank me for 'elping 'islady, sir. Then 'e wanted to see Mr. Warink, sir."

"Why didn't you tell me of this before?" demanded the captain, sternly."You know what happened this morning."

"Hi didn't want to 'ave Mr. Warink suspected, sir," was poor Jeffers'shalf-tearful explanation, as Mr. Allerton suddenly entered the littlehall-way room.

The grave, troubled faces caught his eye at once.

"Is anything wrong?" he inquired, anxiously. "I hope Waring is allright. I tried to induce him not to start, but he said he had promisedand must go."

"What time did he leave you, Mr. Allerton?" asked Cram, controlling asmuch as possible the tremor of his voice.

"Soon after the storm broke,--about nine-thirty, I should say. He triedto get a cab earlier, but the drivers wouldn't agree to go down foranything less than a small fortune. Luckily, his Creole friends had acarriage."

"His what?"

"His friends from near the barracks. They were here when we came downinto the rotunda to smoke after dinner."

Cram felt his legs and feet grow cold and a chill run up his spine.

"Who were they? Did you catch their names?"

"Only one. I was introduced only as they were about to drive away. Alittle old fellow with elaborate manners,--a Monsieur Lascelles."

"And Waring drove away with him?"

"Yes, with him and one other. Seemed to be a friend of Lascelles. Droveoff in a closed carriage with a driver all done up in rubber andoil-skin who said he perfectly knew the road. Why, what's gone amiss?"

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier

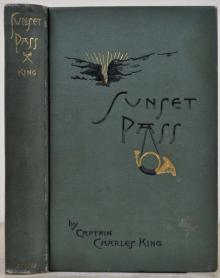

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land

Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days

From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days Annie o' the Banks o' Dee

Annie o' the Banks o' Dee The Black Sea

The Black Sea Under Fire

Under Fire Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier

Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War

Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68.

Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68. Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains A War-Time Wooing: A Story

A War-Time Wooing: A Story The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair

The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair Kitty's Conquest

Kitty's Conquest A Trooper Galahad

A Trooper Galahad Waring's Peril

Waring's Peril Marion's Faith.

Marion's Faith. Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila

Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul