- Home

- Charles King

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains Page 4

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains Read online

Page 4

CHAPTER IV.

SUSPICIOUS CIRCUMSTANCES.

Lieutenant Blunt's position on this bright July morning was mostembarrassing. Personally he had known the pet trumpeter of "B" troopless than a year; for, as was said in the previous chapter, in point ofactual experience on the frontier the boy was the superior of the youngWest Pointer, who had joined only the preceding autumn. Finding youngFred so great a favorite among the officers and men, Mr. Blunt wasquite ready to accept the general verdict, although his first impressionof the youngster was that he was a trifle spoiled. On the other hand noother man in the troop had so favorably impressed the new officer as the"left principal guide," Sergeant Dawson, whose dashing horsemanship,fine figure and carriage, and sharp, soldierly ways had attracted hisattention at the first outset. Then Dawson's manner to him was soscrupulously deferential and soldierly on all occasions--sometimes theold war-worn sergeants would be a trifle supercilious with greensubalterns--that Blunt's moderate amount of vanity was touched. He wasalways glad, when his turn came round as officer of the guard, to findSergeant Dawson on the detail, and he recalled, when he came to thinkover the events of his first half year with the regiment that verysummer, that it was when on guard he began to imagine Fred Waller was"somewhat spoiled." Twice the boy "marched on" as orderly trumpeter whenhe and Dawson were on the guard detail for the day, and both times thesergeant had found fault with the musician, and had most respectfullyand diplomatically, but in that semi-confidential manner which shrewdold soldiers so well know how to assume to very young subalterns, givenMr. Blunt to understand that the boy "needed looking after." Monthslater, when Blunt and Rayburn were discussing the probabilities ofpromotion, when the sergeant-major of the regiment took his dischargeand there was lively competition among the soldiers for this, the finestnon-commissioned post in the regiment, Blunt warmly advocated Dawson'sclaim. "He is the nattiest sergeant in the whole command," he said, "andthe smartest one I know."

"Oh, yes!" answered Rayburn with a certain superiority of manner and aquiet sarcasm that provoked the junior officer; "there's no questionabout Dawson's smartness. One after another every 'plebe' in theregiment starts in with the same enthusiasm about Dawson. I had itmyself about eight years ago. But the trouble with him is he isn't astayer; he can't stand prosperity."

But Blunt preferred to hold to his own views and his faith in the secondsergeant of the troop. And so it happened that on this eventful morninghe sent Sergeant Graham at once to investigate as to the amounts stolenduring the night, and directed that Sergeant Dawson, who was in commandof the herd and picket guard, should come to him immediately.

The sun was just rising above the low treeless ridges on the horizon asthe lieutenant stood erect and looked about him. Close at hand theNiobrara--"the Running Water"--was brawling over its stony shallows, andthe smoke of tiny cook-fires was floating upward into the keen, crisp,morning air. Northward the slopes were bare and treeless, too, butclosely carpeted with the dense growth of buffalo grass. Only a fewyards out from the bivouac, hoppled and sidelined, the troop horses werecropping the still juicy herbage, and three or four soldiers, carbine inhand and garbed in their light-blue overcoats, were posted well outbeyond the herd on every side, watching the valley far and near for anysigns of Indian coming. Below the bivouac, and further from the Laramieroad, was an old log hut, once used as a ranch and "bar" for thirstysouls traversing the well-worn way to the reservation; but the tide oftravel had first shifted to the Sidney route, and then been stemmedentirely, so far as the line to or near the agencies was concerned, andthe proprietor had taken himself and his fiery poison to better-payingfields. Far away to the southwest the blue cone of Laramie Peak stoodboldly against the sky. Nearer at hand, though a day's ride away, oldRawhide Butte rose sturdily from the midst of surrounding prairieslopes. Upstream, among some sparse cottonwood, a bit of ruddy coloramong the branches caught the lieutenant's quick eye. Some Indianbrave, wrapped in his blanket, had been laid to rest there out of reachof the snarling coyotes, one of whom could be dimly discerned slinkingaway under the bank, just out of easy rifle range.

Off to the south lay the same bold, barren, desolate-looking expanse ofrolling prairie. Blunt could not suppress a shudder as he thought of theterrible risk the boy had run in his mad break for the settlementsbeyond the Platte. Of course he could go nowhere else. North, east, andwest, all was Indian land, and no lone white man could live there. Ofcourse he was making for the cattle ranges and settlements in Nebraska.Such at least were the lieutenant's theories. He had spent only one yearon the frontier, but had been there long enough to know that among thecowboys, ranchmen, and especially among the "riff-raff" ever hangingabout the small towns and settlements, a deserter from the army was aptto be welcomed and protected, if he had money, arms, or a good horse.Once plundered of all he possessed, the luckless fellow might then beturned over to the nearest post and the authorized reward of thirtydollars claimed for his apprehension; but if well armed and sober, thedeserter had little trouble in making his way through the toughestmining camps and settlements.

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier

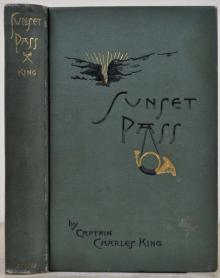

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land

Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days

From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days Annie o' the Banks o' Dee

Annie o' the Banks o' Dee The Black Sea

The Black Sea Under Fire

Under Fire Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier

Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War

Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68.

Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68. Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains A War-Time Wooing: A Story

A War-Time Wooing: A Story The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair

The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair Kitty's Conquest

Kitty's Conquest A Trooper Galahad

A Trooper Galahad Waring's Peril

Waring's Peril Marion's Faith.

Marion's Faith. Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila

Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul