- Home

- Charles King

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul Page 4

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul Read online

Page 4

In later years, Ottoman subjects would come to regret the slide toward what became known as the First World War, blaming it on the machinations of the Unionists and the prodding of Berlin. But war fever and a wave of patriotism swept through the imperial capital. Ottoman soldiers were mobilized on all fronts as the Allies laid plans for a two-pronged attack on the empire: a rush through the Balkans to threaten Istanbul and a push westward from the Russian Caucasus to engage Ottoman positions in eastern Anatolia. Initial engagements on both fronts produced no lightning victories for either side. The tumble toward war quickly became a scramble for new allies, as the warring parties sought to persuade neutral countries—Greece, Bulgaria, and Romania—to enter on their side.

The Allies and the Central Powers alike used the promise of territory and postwar freedom as levers to win and keep support. The Arabs would be free of the sultan’s control, the Allies declared. Russia would be awarded Istanbul and strategic access to the Mediterranean via the Bosphorus and Dardanelles Straits. Britain, France, and Russia would divide up much of eastern Anatolia, Syria, and Mesopotamia. Greece would have a share of the Aegean coast. For average Ottoman soldiers, these prospective territorial arrangements—made in secret but abundantly clear to everyone at the time—quickly turned the war into a struggle for survival. The potential costs were apparent: the end of the Ottoman Empire, the dismemberment of the state, and perhaps even the loss of the imperial capital itself.

“Ayesha, angel of beauty,” an Ottoman infantry captain wrote to his wife a few months after the war began.

We are bombarded here by the English. No rest we receive and very little food and our men are dying by hundreds from disease. Discontent is also beginning to show itself among the men, and I pray God to bring this all to an end. I can see lovely Constantinople in ruins and our children put to the sword and nothing but some great favor from God can stop it. . . . Oh, why did we join in this wicked war?

The letter was found on the captain’s body after the fighting between Ottoman and British imperial forces in the campaign at Gallipoli, down the western peninsula from Istanbul. Gallipoli had been intended as the first phase of an Allied march on the capital, an effort to secure control of the Dardanelles and slowly choke off Istanbul from resupply via the Mediterranean. But for much of 1915, poor planning and heavy resistance by Ottoman field commanders kept Allied soldiers pinned down in ravines and scrubland along the coast, sometimes only steps away from their initial landing sites. When the Allies finally called a halt to the operation, the victory was a substantial one for the Ottomans, but it was extracted at a brutal cost. As many as three-quarters of a million men on both sides had been engaged at Gallipoli, and the grueling fighting illustrated the vulnerability of the capital to land and sea attack. Mines had been floated in the Straits, bringing the normally vibrant sea trade to a halt. The carcasses of Allied battleships poked out of the water and clogged the sea-lane.

Throughout the war, the Unionists, working inside the Ottoman state administration, sought to provoke Muslim revolts abroad, using the sultan’s role as caliph to inspire Muslims in the Russian Caucasus, French North Africa, and British India to rise up against their governments. The British tried to do the same among the sultan’s Arab subjects, most famously through the exploits of the adventurer T. E. Lawrence. None of these projects fully succeeded, but the connection between domestic politics and foreign intrigue remained a particular concern of Unionist leaders. Officials were intent on uncovering alleged fifth columns sympathetic to the Allies’ territorial goals. In eastern Anatolia, military units and irregular militias organized the roundup and deportation of entire villages of Armenians and other Eastern Christians who were thought to be potentially loyal to Russia. Armenian revolutionary groups had in fact organized uprisings in Armenian-populated areas of the empire; some had even operated openly in Istanbul and, in 1896, had staged a spectacular raid on the Imperial Ottoman Bank, just downhill from the Grande Rue. But the military and political establishment around the leaders Enver, Cemal, and Talât, especially the so-called Special Organization within the Committee of Union and Progress, responded with a mass campaign of death.

The Special Organization’s chief task was to organize paramilitary units under the command of the army and eliminate potential enemies of the state. Once Ottoman forces began to experience major defeats on the eastern front, especially after the decisive battle with Russian forces at Sarikamish in December 1914–January 1915, the Special Organization and its sympathizers moved to eliminate Armenians who were thought responsible for undermining the war effort. By March, Unionist leaders had taken the decision to kill or deport hundreds of thousands of Armenians in sensitive border regions and to arrest or assassinate key civic and political leaders within the Armenian community. The Unionist sons of Muslim refugees from the Balkans, pushed out of former Ottoman lands in the 1870s, now orchestrated a similar fate for Ottoman Christians. On the night of April 24–25, 1915, more than two hundred Armenian intellectuals and community leaders were deported from Istanbul to the Anatolian countryside. Some were already refugees from anti-Armenian violence in the east and had come to the capital to seek refuge and redress with the central government. Grigoris Balakian, an Armenian priest, recalled sitting in the central prison with many of the major figures in Istanbul’s Armenian community—parliamentarians, editors, teachers, doctors, dentists, and bankers—along with average men and boys caught up in the frenzy of violence. He was soon sent to central Anatolia, where he began a long odyssey of forced marches, imprisonment, and abuse. He managed to return to Istanbul three years later but then only in the disguise of a German soldier.

Balakian compiled a record of his sufferings and the fates of friends, victims, and collaborators. He was among the fortunate ones, he said, who, “thanks to large bribes or powerful and influential connections, succeeded in returning to Constantinople and were saved.” Many of the others perished. Even for the escapees, however, scars remained. Gomidas Vardabed, the premier Armenian liturgical composer and choral master, was allowed to return to the capital, but he soon fled to Paris and, year by year, descended into madness. He died in a French psychiatric hospital.

Meanwhile, more roundups followed in Istanbul. Tripod scaffolds were set up outside the grand Kılıç Ali Pasha mosque near the Bosphorus, where Armenians and others were hanged for sedition as crowds of men, women, children, and a few German soldiers looked on. In the end, it was perhaps only because of pressure from German officials—who feared the impact that disorderly lynchings and deportations would have on the war effort—that the rest of Istanbul’s Armenian population was spared from removal. However, over the course of the war, anti-Armenian violence and deportation policies led to the near-wholesale elimination of the Armenian presence in Anatolia and the deaths of somewhere between six hundred thousand and more than a million Ottoman Christians.

The genocidal attacks were meant to facilitate a new wave of Ottoman battlefield victories, but military losses over the next three years whittled away at Ottoman positions. New offensives against Greece in the Balkans and Russia in the Caucasus ground to a halt. To the south, in Mesopotamia and Palestine, Ottoman armies were in disarray, facing the loss of Damascus and outgunned by British imperial troops. Germany was bogged down on the western front, besieged by a new Allied offensive there.

In Istanbul, raids increased on houses belonging to British and French expatriates. The harbor remained empty, with shipping blocked by the effective closure of the Dardanelles and Russian patrols on the Black Sea. Coal was scarce, and the gasworks were closed, often leaving the city in blackness at night. Police permits were required to buy more than one loaf of bread per day, and fights frequently erupted at bakeries. Even then, the loaves on offer were sometimes made from a rank mixture of flour and straw. An infestation of venomous lice sickened thousands and kept people out of crowded tramcars or other enclosed spaces.

Earlier in the war, the empire’s neighbor to the west,

Bulgaria, had opted to join the Ottomans on the side of the Central Powers. But in September 1918, Istanbul newspapers carried stunning news. Facing its own battlefield losses and hemmed in on nearly all sides, Bulgaria agreed to sign a separate armistice with the Allies. The Ottomans’ western shield was now gone, and Istanbul lay within easy marching distance of the Hellenic border, where Allied troops were already massed. The Ottoman government soon approached the British with a desire to negotiate an end to hostilities.

Over three days in October, representatives of the British War Office met with their Ottoman counterparts on the battleship Agamemnon, anchored off Mudros in the Aegean Sea. On October 30, they signed the armistice that ended the fighting between the sultan’s empire and the major Allied powers. Just under two weeks later—at the eleventh hour, of the eleventh day, of the eleventh month—Germany signed an armistice as well, bringing the First World War to a close. News of the full cessation of hostilities raced through the streets of Istanbul, but locals barely had time to contemplate what lay ahead for their defeated country. The Allies had arrived to tell them.

On the overcast morning of November 13, 1918, a fleet of steel-hulled battleships sailed into the Bosphorus from the south. Large naval ensigns, specially unfurled for the event, flew from their mainmasts. At the front came the British flagship Superb, followed by the Temeraire, Lord Nelson, and Agamemnon, along with five British cruisers and several destroyers. French dreadnoughts followed close behind, while Italian cruisers and Hellenic destroyers brought up the rear.

As far as one could see, the water was choked with gray ships. “The grand sight of the combined British-French-Italian and Greek Naval Squadrons slowly and majestically steaming into the Bosphorus, thus breaking (I trust for ever) Turkish tyranny—men and women met and shook hands but could not speak—the joyous excitement was immense amongst the Christian population,” wrote a British eyewitness. It was the largest and deadliest contingent of armed foreign vessels ever to reach the city.

Around 8:00 a.m., admirals and captains ordered the anchors dropped. Sailors on board looked out and saw the impressive line of coastal guns and other defenses behind the ancient sea walls. Although the ships were within easy artillery range of four of the sultan’s palaces, they met no resistance.

The victors were now making a show of force against their former opponent, steaming straight into the heart of the Ottoman city. None of the other enemy capitals in the war—Berlin, Vienna, Sofia—played host to so much Allied firepower. The newcomers saw themselves not just as winners but as liberators, sent on a providential mission to unburden the people of Istanbul of their benighted government and free the Christians of the city from Muslim rule. “It was a sight one was glad to have been privileged to see,” said Able Seaman F. W. Turpin, a gunner aboard the Agamemnon.

Not everyone agreed. Musbah Haidar, the daughter of the emir of Mecca, joined the tens of thousands crowding the heights above the Bosphorus to witness the arrival of the Allied force. She was a relative of the imperial family, and her father was the official guardian of the holiest city in Islam. She watched from her family’s mansion as the Hellenic flagship Averoff sailed right up to the imperial quay at the sultan’s Dolmabahçe Palace. Local Greek Orthodox inhabitants “were in an ecstasy of excitement,” Musbah recalled, while Muslims like herself “looked on dazed . . . their empire broken.”

Muslim refugees fleeing from fighting in the Balkans had built a shantytown around the footings of the ancient Aqueduct of Valens. Families had flattened discarded oilcans and used them to build walls and roofs against the winter rains, making entire neighborhoods look like giant advertisements for Standard Oil. Grigoris Balakian, the disguised priest who had been deported from the city during the Armenian genocide, crossed the Bosphorus in a rowboat just as the ships were entering the strait. “Effendi, what bad times we’re living in!” said his Muslim boatman. “Who would have believed that a foreign fleet would enter Constantinople so illustriously and that we Muslims would be simple spectators?”

Over the following days and weeks, French officers in blue-corded kepis marched down the streets of the old city beside British comrades in khaki field dress and steel helmets. Senegalese infantrymen and Italian bersaglieri, the long plumes on their hats blowing in the breeze, patrolled the Grande Rue. General George Milne, the senior officer in the British contingent, took up residence at the Pera Palace before moving to a waterfront house in the suburb of Tarabya requisitioned from Krupp, the German steel conglomerate. Later, the French commander, General Louis Franchet d’Espèrey, made a ceremonial entry into the city on a white horse, only to discover that British General Edmund Allenby had trumped him by doing the same thing the previous day. He consoled himself by moving into an exiled pasha’s residence in the pleasant village of Ortaköy. “It was . . . like having two prima donnas on the stage together,” recalled Tom Bridges, a British liaison officer, “and the play went much better if we could keep one in her dressing room.”

The city was soon divided into zones of control headed by representatives of the principal Allied powers. The British were to oversee Pera and Galata, the French the old city south of the Golden Horn, and the Italians the Asian suburbs in Üsküdar. A combined force assumed control of the city’s police. Allied high commissions would later be appointed to try criminals, oversee port activity, inspect and maintain the prisons, provide for public sanitation, govern hospital and convalescence facilities for Allied troops, and supervise the demobilization and disarmament of Ottoman soldiers.

By the time the Allies steamed into the Bosphorus, the Unionist triumvirate of Enver, Cemal, and Talât had already fled the capital aboard a German submarine. None would be around to witness the occupation. Three years later, Talât was gunned down by an Armenian assassin on the streets of Berlin, an act of revenge for his role in the genocide. Cemal was killed the following year in Tbilisi, also by an Armenian, while Enver died attempting to rouse Muslims against the Bolsheviks in Central Asia.

By the time the Superb dropped anchor, the Ottoman Empire had existed for six hundred nineteen years. When the Allied fleet sailed into port, the sitting monarch, Sultan Mehmed VI—who had ascended the throne upon his brother’s death in July 1918—counted himself the thirty-sixth member of a dynastic line running back to its founder, Osman (from which Westerners had derived the mispronounced label “Ottoman”). He shared his name with both the fifteenth-century conqueror of Constantinople, Mehmed II, and the Prophet Muhammad. His distant ancestors had been Turkic tribal leaders and Circassian slaves, but around the world, hundreds of millions of Muslims looked to him as successor to the Prophet and the earthly leader of the one true faith.

Istanbul had long been “the principal storm center of Europe and Asia,” declared a briefing book for American naval personnel, who soon arrived in the city as part of the Allied contingent. Muslims had “misguided the city through a colorful and turbulent career, . . . giving it a more or less malodorous reputation in international affairs.” Now it would be supervised by benevolent Western powers until a final peace settlement could be reached and the fate of the powerless Ottoman Empire determined.

As Allied officers worked to set up their administration, the coldest winter in living memory descended on the city. The Spanish flu began to sicken locals and foreigners alike. Looters ransacked unguarded mansions. A Turkish-speaking Muslim, Ziya Bey, witnessed the first months of the occupation. He was relatively new to Istanbul, but he would in no sense have put himself in the same category as the refugees and Allied soldiers who were streaming into the city. He was born in Niantaı, the fashionable district to the north of Pera, surrounded by quiet avenues and ornate, fin-de-siècle apartment buildings. His family spent summers on the Princes Islands in the Sea of Marmara, an easy ferry ride from the docklands of central Istanbul and a traditional summering spot for Greeks, Armenians, and the few Muslims who were able to afford property there.

When Ziya was still a boy, shortly before the Fir

st World War, his father collected the family and decamped for New York to look after his export businesses. In America, Ziya met a young woman, originally from New Orleans, and fell in love. The two were married a short time later. With the war over and trade beginning to pick up again, new opportunities called the family back to Istanbul. The political future was still uncertain, but Ziya must have reckoned that being around for the beginning of whatever kind of country would replace the old empire was a reasonable bet, especially for an ambitious, cosmopolitan young man seeking to move out from under his father’s shadow.

Istanbul was not the same city he had left, however. “Greedy or inviting glances” followed him everywhere. Civilian refugees, skinny and often clothed in little more than rags, mixed with maimed Ottoman soldiers, some still wearing uniforms and battle decorations. Destitute people sold old wooden toys, artificial flowers, candies, and newspapers to passersby. On one corner, a young mother, sad-looking and visibly pregnant, leaned against a wall and held out a bouquet of multicolored balloons. Children slept on curbs and in doorways before being moved along by an Allied patrol.

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier

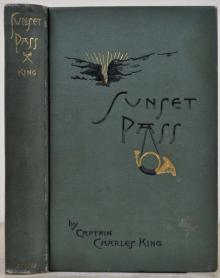

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land

Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days

From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days Annie o' the Banks o' Dee

Annie o' the Banks o' Dee The Black Sea

The Black Sea Under Fire

Under Fire Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier

Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War

Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68.

Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68. Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains A War-Time Wooing: A Story

A War-Time Wooing: A Story The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair

The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair Kitty's Conquest

Kitty's Conquest A Trooper Galahad

A Trooper Galahad Waring's Peril

Waring's Peril Marion's Faith.

Marion's Faith. Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila

Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul