- Home

- Charles King

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Page 11

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Read online

Page 11

CHAPTER XI

A STOP--BY WIRE

Three days later the infantry guard of the garrison were in solecharge. Wren and Sanders, with nearly fifty troopers apiece, had takenthe field in compliance with telegraphic orders from Prescott. Thegeneral had established field headquarters temporarily at CampMcDowell, down the Verde Valley, and under his somewhat distantsupervision four or five little columns of horse, in single file, wereboring into the fastnesses of the Mogollon and the Tonto Basin. Therunners had been unsuccessful. The renegades would not return. Half adozen little nomad bands, forever out from the reservation, hadeagerly welcomed these malcontents and the news they bore that two oftheir young braves had been murdered while striving to defend Natzieand Lola. It furnished all that was needed as excuse for instantdescent upon the settlers in the deep valleys north of the Rio Salado,and, all unsuspecting, all unprepared, several of these had met theirdoom. Relentless war was already begun, and the general lost no timein starting his horsemen after the hostiles. Meantime the infantrycompanies, at the scattered posts and camps, were left to "hold thefort," to protect the women, children, and property, and Neil Blakely,a sore-hearted man because forbidden by the surgeon to attempt to go,was chafing, fuming, and retarding his recovery at his lonelyquarters. The men whom he most liked were gone, and the few among thewomen who might have been his friends seemed now to stand afar off.Something, he knew not what, had turned garrison sentiment againsthim.

For a day or two, so absorbed was he in his chagrin over Graham'sverdict and the general's telegraphic orders in the case, Mr. Blakelynever knew or noticed that anything else was amiss. Then, too, therehad been no opportunity of meeting garrison folk except the fewofficers who dropped in to inquire civilly how he was progressing. Thebandages were off, but the plaster still disfigured one side of hisface and neck. He could not go forth and seek society. There wasreally only one girl at the post whose society he cared to seek. Hehad his books and his bugs, and that, said Mrs. Bridger, was "all hedemanded and more than he deserved." To think that the very room sorecently sacred to the son and heir should be transformed into whatthat irate little woman called a "beetle shop"! It was one of Mr.Blakely's unpardonable sins in the eyes of the sex that he found somuch to interest him in a pursuit that neither interested nor includedthem. A man with brains and a bank account had no right to live alone,said Mrs. Sanders, she having a daughter of marriageable age, if onlymoderately prepossessing. All this had the women to complain of in himbefore the cataclysm that, for the time at least, had played havocwith his good looks. All this he knew and bore with philosophic andwhimsical stoicism. But all this and more could not account for thephenomenon of averted eyes and constrained, if not freezing, mannerwhen, in the dusk of the late autumn evening, issuing suddenly fromhis quarters, he came face to face with a party of four young womenunder escort of the post adjutant--Mrs. Bridger and Mrs. Trumanforemost of the four and first to receive his courteous, yet halfembarrassed, greeting. They had to stop for half a second, as theylater said, because really he confronted them, all unsuspected. Butthe other two, Kate Sanders and Mina Westervelt, with bowed heads andwithout a word, scurried by him and passed on down the line. Dotyexplained hurriedly that they had been over to the post hospital toinquire for Mullins and were due at the Sanders' now for music,whereupon Blakely begged pardon for even the brief detention, and,raising his cap, went on out to the sentry post of No. 4 to study thedark and distant upheavals in the Red Rock country, where, almostevery night of late, the signal fires of the Apaches were reported.Not until he was again alone did he realize that he had been almostfrigidly greeted by those who spoke at all. It set him to thinking.

Mrs. Plume was still confined to her room. The major had returned fromPrescott and, despite the fact that the regiment was afield and aclash with the hostiles imminent, was packing up preparatory to amove. Books, papers, and pictures were being stored in chests, big andlittle, that he had had made for such emergencies. It was evidentthat he was expecting orders for change of station or extended leave,and they who went so far as to question the grave-faced soldier, whoseemed to have grown ten years older in the last ten days, had to becontent with the brief, guarded reply that Mrs. Plume had never beenwell since she set foot in Arizona, and even though he returned, shewould not. He was taking her, he said, to San Francisco. Of thisunhappy woman's nocturnal expedition the others seldom spoke now andonly with bated breath. "Sleep-walking, of course!" said everybody, nomatter what everybody might think. But, now that Major Plume knew thatin her sleep his wife had wandered up the row to the very door--theback door--of Mr. Blakely's quarters, was it not strange that he hadtaken no pains to prevent a recurrence of so compromising anexcursion, for strange stories were afloat. Sentry No. 4 had heard andtold of a feminine voice, "somebody cryin' like" in the darkness ofmidnight about Blakely's, and Norah Shaughnessy--returned to herduties at the Trumans', yet worrying over the critical condition ofher trooper lover, and losing thereby much needed sleep--had gainedsome new and startling information. One night she had heard, anothernight she had dimly seen, a visitor received at Blakely's back door,and that visitor a woman, with a shawl about her head. Norah told hermistress, who very properly bade her never refer to it again to asoul, and very promptly referred to it herself to several souls, oneof them Janet Wren. Janet, still virtuously averse to Blakely, laidthe story before her brother the very day he started on the warpath,and Janet was startled to see that she was telling him no newswhatever. "Then, indeed," said she, "it is high time the major tookhis wife away," and Wren sternly bade her hold her peace, she knew notwhat she was saying! But, said Camp Sandy, who could it have been butMrs. Plume or, possibly, Elise? Once or twice in its checkered pastCamp Sandy had had its romance, its mystery, indeed its scandals, butthis was something that put in the shade all previous episodes; thisshook Sandy to its very foundation, and this, despite her brother'sprohibition, Janet Wren felt it her duty to detail in full to Angela.

To do her justice, it should be said that Miss Wren had strivenvaliantly against the impulse,--had indeed mastered it for severalhours,--but the sight of the vivid blush, the eager joy in the sweetyoung face when Blakely's new "striker" handed in a note addressed toMiss Angela Wren, proved far too potent a factor in the undoing ofthat magnanimous resolve. The girl fled with her prize, instanter, toher room, and thither, as she did not reappear, the aunt betookherself within the hour. The note itself was neither long noreffusive--merely a bright, cordial, friendly missive, protestingagainst the idea that any apology had been due. There was but one linewhich could be considered even mildly significant. "The little net,"wrote Blakely, "has now a value that it never had before." Yet Angelawas snuggling that otherwise unimportant billet to her cheek when thecreaking stairway told her portentously of a solemn coming. Tenminutes more and the note was lying neglected on the bureau, andAngela stood at her window, gazing out over dreary miles of almostdesert landscape, of rock and shale and sand and cactus, with eyesfrom which the light had fled, and a new, strange trouble biting ather girlish heart. Confound No. 4--and Norah Shaughnessy!

It had been arranged that when the Plumes were ready to start, Mrs.Daly and her daughter, the newly widowed and the fatherless, should besent up to Prescott and thence across the desert to Ehrenberg, on theColorado. While no hostile Apaches had been seen west of the VerdeValley, there were traces that told that they were watching the roadas far at least as the Agua Fria, and a sergeant and six men had beenchosen to go as escort to the little convoy. It had been supposed thatPlume would prefer to start in the morning and go as far as Stemmer'sranch, in the Agua Fria Valley, and there rest his invalid wife untilanother day, thus breaking the fifty-mile stage through the mountains.To the surprise of everybody, the Dalys were warned to be in readinessto start at five in the morning, and to go through to Prescott thatday. At five in the morning, therefore, the quartermaster's ambulancewas at the post trader's house, where the recently bereaved ones hadbeen harbored since poor Daly's death, and there, wit

h their generoushost, was the widow's former patient, Blakely, full of sympathy andsolicitude, come to say good-bye. Plume's own Concord appeared almostat the instant in front of his quarters, and presently Mrs. Plume,veiled and obviously far from strong, came forth leaning on herhusband's arm, and closely followed by Elise. Then, despite the earlyhour, and to the dismay of Plume, who had planned to start withoutfarewell demonstration of any kind, lights were blinking in almostevery house along the row, and a flock of women, some tender andsympathetic, some morbidly curious, had gathered to wish the major'swife a pleasant journey and a speedy recovery. They loved her not atall, and liked her none too well, but she was ill and sorrowing, sothat was enough. Elise they could not bear, yet even Elise came in fora kindly word or two. Mrs. Graham was there, big-hearted and brimmingover with helpful suggestion, burdened also with a basket of dainties.Captain and Mrs. Cutler, Captain and Mrs. Westervelt, the Trumansboth, Doty, the young adjutant, Janet Wren, of course, and the ladiesof the cavalry, the major's regiment, without exception, were on handto bid the major and his wife good-bye. Angela Wren was not feelingwell, explained her aunt, and Mr. Neil Blakely was conspicuous by hisabsence.

It had been observed that, during those few days of hurried packingand preparation, Major Plume had not once gone to Blakely's quarters.True, he had visited only Dr. Graham, and had begged him to explainthat anxiety on account of Mrs. Plume prevented his making the roundof farewell calls; but that he was thoughtful of others to the lastwas shown in this: Plume had asked Captain Cutler, commander of thepost, to order the release of that wretch Downs. "He has beenpunished quite sufficiently, I think," said Plume, "and as I wasinstrumental in his arrest I ask his liberation." At tattoo,therefore, the previous evening "the wretch" had been returned toduty, and at five in the morning was found hovering about the major'squarters. When invited by the sergeant of the guard to explain, hereplied, quite civilly for him, that it was to say good-by to Elise."Me and her," said he, "has been good friends."

Presumably he had had his opportunity at the kitchen door before thestart, but still he lingered, feigning professional interest in thecondition of the sleek mules that were to haul the Concord over fiftymiles of rugged road, up hill and down dale before the setting of thesun. Then, while the officers and ladies clustered thick on one sideof the black vehicle, Downs sidled to the other, and the big blackeyes of the Frenchwoman peered down at him a moment as she leanedtoward him, and, with a whispered word, slyly dropped a little foldedpacket into his waiting palm. Then, as though impatient, Plume shouted"All right. Go on!" The Concord whirled away, and something like asigh of relief went up from assembled Sandy, as the first kiss of therising sun lighted on the bald pate of Squaw Peak, huge sentinel ofthe valley, looming from the darkness and shadows and the mists of theshallow stream that slept in many a silent pool along its massive,rocky base. With but a few hurried, embarrassed words, Clarice Plumehad said adieu to Sandy, thinking never to see it again. They stoodand watched her past the one unlighted house, the northernmost alongthe row. They knew not that Mr. Blakely was at the moment biddingadieu to others in far humbler station. They only noted that, even atthe last, he was not there to wave a good-by to the woman who had onceso influenced his life. Slowly then the little group dissolved anddrifted away. She had gone unchallenged of any authority, though thefate of Mullins still hung in the balance. Obviously, then, it was notshe whom Byrne's report had implicated, if indeed that report hadnamed anybody. There had been no occasion for a coroner and jury.There would have been neither coroner nor jury to serve, had they beencalled for. Camp Sandy stood in a little world of its own, the onlycivil functionary within forty miles being a ranchman, dwelling sevenmiles down stream, who held some Territorial warrant as a justice ofthe peace.

But Norah Shaughnessy, from the gable window of the Trumans' quarters,shook a hard-clinching Irish fist and showered malediction after theswiftly speeding ambulance. "Wan 'o ye," she sobbed, "dealt PatMullins a coward and cruel blow, and I'll know which, as soon as everthat poor bye can spake the truth." She would have said it to thathated Frenchwoman herself, had not mother and mistress both forbadeher leaving the room until the Plumes were gone.

Three trunks had been stacked up and secured on the hanging rack atthe rear of the Concord. Others, with certain chests and boxes, hadbeen loaded into one big wagon and sent ahead. The ambulance, withthe Dalys and the little escort of seven horsemen, awaited the rest ofthe convoy on the northward flats, and the cloud of their combineddust hung long on the scarred flanks as the first rays of the risingsun came gilding the rocks at Boulder Point, and what was left of thegarrison at Sandy turned out for reveille.

That evening, for the first time since his injury, Mr. Blakely tookhis horse and rode away southward in the soft moonlight, and had notreturned when tattoo sounded. The post trader, coming up with thelatest San Francisco papers, said he had stopped a moment to ask atthe store whether Schandein, the ranchman justice of the peace beforereferred to, had recently visited the post.

That evening, too, for the first time since his dangerous wound,Trooper Mullins awoke from his long delirium, weak as a little child;asked for Norah, and what in the world was the matter with him--in bedand bandages, and Dr. Graham, looking into the poor lad's dim,half-opening eyes, sent a messenger to Captain Cutler's quarters toask would the captain come at once to hospital. This was at nineo'clock.

Less than two hours later a mounted orderly set forth with dispatchesfrom the temporary post commander to Colonel Byrne at Prescott. A wirefrom that point about sundown had announced the safe arrival of theparty from Camp Sandy. The answer, sent at ten o'clock, broke up thegame of whist at the quarters of the inspector general. Byrne, therecipient, gravely read it, backed from the table, and vainly strovenot to see the anxious inquiry in the eyes of Major Plume, his guest.But Plume cornered him.

"From Sandy?" he asked. "May I read it?"

Byrne hesitated just one moment, then placed the paper in his junior'shand. Plume read, turned very white, and the paper fell from histrembling fingers. The message merely said:

Mullins recovering and quite rational, though very weak. He says two women were his assailants. Courier with dispatches at once.

(Signed) CUTLER, Commanding.

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier

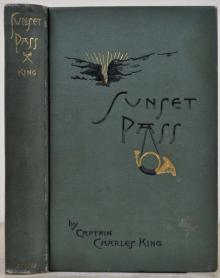

A Daughter of the Sioux: A Tale of the Indian frontier Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land

Sunset Pass; or, Running the Gauntlet Through Apache Land From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days

From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days Annie o' the Banks o' Dee

Annie o' the Banks o' Dee The Black Sea

The Black Sea Under Fire

Under Fire Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier

Starlight Ranch, and Other Stories of Army Life on the Frontier Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War

Tonio, Son of the Sierras: A Story of the Apache War An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier

An Apache Princess: A Tale of the Indian Frontier Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68.

Warrior Gap: A Story of the Sioux Outbreak of '68. Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains

Trumpeter Fred: A Story of the Plains A War-Time Wooing: A Story

A War-Time Wooing: A Story The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair

The Adventures of a Country Boy at a Country Fair Kitty's Conquest

Kitty's Conquest A Trooper Galahad

A Trooper Galahad Waring's Peril

Waring's Peril Marion's Faith.

Marion's Faith. Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila

Ray's Daughter: A Story of Manila Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul

Midnight at the Pera Palace_The Birth of Modern Istanbul